Originally published in Essentially MIDIRS 2011; 2(9): 47-49. Revised

As I compiled the statistics of my home birth practice covering a 22 year period many of the individual instances of how my knowing developed became definable – the watershed moments which influenced my ongoing practice. This post elaborates two such moments during the care of one woman, relating to both meconium-stained liquor (MSL) and as to how I position myself with women.

gardenofholiness.blogspot.co.nz/2012_06_01_archive.html

This began with a phone call from the husband of a woman I will call Arlene informing me, “the waters have broken and they’re slightly cloudy.”

Exploring ‘slightly cloudy’ revealed a picture of meconium-stained liquor in early labour which warranted an immediate visit to Arlene, now at term with her first baby. I contemplated the unknowable as I drove to her home nearly 25 years ago – was this baby just one of the nearly 9-12 percent of babies who pass meconium in labour Katz & Bowes (1992); Paul et al (1989)? Would he ‘escape’ meconium aspiration syndrome (MAS)? Meconium-stained liquor had always been written in red on the ubiquitous Delivery Suite board as a flag reminding all that this baby ‘needed’ a paediatrician at birth in what had beome a ‘high risk’ labour. It was this culture that I had initially brought with me when I commenced home birth practice in 1989. As I drove to her home, I was comforted by the knowledge that Arlene was well and her baby was moving but I felt disappointed at the thought that I would be recommending transfer to hospital from her planned home birth.

The towel which Arlene had used to mop up the liquor showed heavy, fresh meconium-staining; her pad exhibited fresh smudges. Palpating her abdomen, her baby, who had been in an LOP position at our last visit 5 days earlier, was now ROL with his head not yet fixed in the pelvis. Listening to the heart beat indicated a baby who was coping well with labour, which was now well established. As part of the routine assessment I had used when attending women in hospital, and which I used early in my home birth practice (though soon abandoned), I performed the ritual vaginal examination. This revealed a very posterior, closed and thick cervix; I could only just tip the baby’s head with my finger. This information did not tally with the strength and frequency of Arlene’s contractions; her cervix had not ‘caught up’ with the labouring she was doing.

Following this assessment and some discussion, I recommended that we transfer to the obstetric hospital so I could “monitor the baby closely and suction him at birth”.

“Can’t you do that here?” she enquired.

“Well – yes – I can,” I responded. I was skilled in intermittent auscultation, and over 2 years working in a neonatal intensive care unit prior to midwifery registration had honed my suctioning skills.

“Then, I don’t want to go to the hospital!”

Arlene would birth at home nearly 9 hours later, her baby having rotated progressively into an LOA position prior to birth. Throughout labour, the baby had continued to move and his heart tones, the rate of which never missed a beat, were punctuated with early accelerations as the contractions started, with a return to his normal baseline heart rate following contractions. The release of the meconium had been an early labour incident only, perhaps as a stress response to his head being firmly pressed while pivoting on an initially ‘unyielding’ cervix; by the time of birth there was only faintly stained, old meconium present. I had suctioned him once his head was born over the perineum, again simply following the ritual used in the obstetric hospital from which I had recently departed. Baby had excellent Apgars and required no further ‘treatment’. Arlene was aware of what his normal breathing pattern should be and would contact me if she had any concerns about his breathing, which did not occur.

Getting to grips with meconium-stained liquor

As has repeatedly happened over the decades following an ‘out of the ordinary’ practice experience, I began a ‘watching brief’ of the literature, this time on meconium-stained liquor. By 2009, midwifery colleagues around New Zealand reported that the practice of oro- or naso-pharngeal suctioning of newborns was no longer a routine treatment for MSL, but this was 5 years after publication of the Vain and colleagues’ Vain et al (2004) large randomised controlled trial (n=2514) concluding that suctioning does not prevent MAS; the change had coincided with the 2009 instructional message Vain et al (2009) to desist from the practice. This was nearly two decades after the Linder et al (1988) prospective study of 572 vigorous newborns with MSL determined no benefit and, indeed, harm to newborns in suctioning under view, a finding supported by Paul et al (1989), and a decade after meta-analysis confirmed the lack of evidence in suctioning vigorous newborns to prevent MAS Halliday & Sweet (1999). I had also found a lack of evidence to support which equipment to use – bulb syringe or DeLee suction Locus et al (1990), yet penetrating suction catheters which damaged delicate mucous membranes and initiated bradycardias following stimulation of the vagal nerve continued to be used in my region, and babies continued to be suctioned on the perineum despite a lack of difference to the incidence of MAS shown between late or early suctioning Falciglia et al (1992). No correlation was found between consistency of meconium and MAS Trimmer & Gilstrap (1991) in the early 1990s, yet, as mentioned previously, routine suctioning to prevent MAS did not appear to change in New Zealand hospitals till 2009. It was as if a routine intervention could effectively be introduced immediately with no or minimal evidence to support it but an intervention could only be withdrawn after decades of papers being published indicating a lack of benefit or actual harm relating to the intervention.

A year of tracking this early literature after Arlene’s labour and seeing how little of the evidence was incorporated into the ‘routine’ care of meconium exposed infants was the initiator for me to no longer rely on protocols or guidelines but to instead search out the evidence myself. As a result, my own practice changed. That year coincided with me starting to value my own midwifery experiences as another valid form of evidence. I witnessed babies coughing on the perineum and meconium-stained liquor draining freely from babies’ mouths and noses prior to birth and it made me further question the value of suctioning in the presence of meconium in an otherwise normal labour.

I also stopped recommending transfer to hospital with MSL in the absence of abnormal heart tones, though, for the majority of the time, there was no real option of transfer as the membranes tended to rupture with the onset of spontaneous pushing or following birth of the baby’s head. I came to believe that this timing was probably the result of avoiding unnecessary vaginal examinations in labour and, therefore, avoiding exposure of the amniotic membranes to synthetic substances, such as latex or vinyl, which may weaken them.

A practice that also changed was the other thread to Arlene’s story.

Securing my withWoman position

During Arlene’s labour her decision to remain at home sat well with me but this incident happened prior to the return of midwifery autonomy in New Zealand in September 1990. It was a time when midwives were required to have a medical practitioner over-see their practice, including domiciliary midwives, as homebirth midwives were then known. This was an in limbo time when midwives did not have access agreements to provide services in hospital and the very few of us who practised in homebirth did so with varying degrees of support or obstruction from hospital staff Banks (2007).

clipart-finder.com/clipart/scalesofjustice646.html

With Arlene’s declining hospital transfer, I had felt in a tricky position. While the general practitioner was comfortable with the refusal to transfer, he did not practise obstetrics in the local hospital and I knew he would not experience the fallout if transfer was needed later in labour. Rather than seeking instruction on what to do, I wanted to try to temper the criticism of my practice that would eventuate from the staff at the obstetric hospital. I wanted to engender support for myself from an obstetrician. The fallout from transfer was costly for both midwives and the women they cared for with horizontal violence being a common occurrence in transfer situations Banks (2007). I discussed my plan with Arlene, and she supported my proposed action.

Explaining the situation to the midwife in charge of the Delivery Suite and the on-call consultant obstetrician, I was instructed to continue recommending transfer to hospital throughout the labour. If Arlene continued to decline transfer I should, the obstetrician advised, get the general practitioner to accept responsibility if the advice was not accepted.

This ‘advice’ was unacceptable on three levels. Firstly, to repeatedly recommend transfer to hospital throughout the labour when Arlene had made her decision was – in real terms – a bullying tactic to ensure she acquiesced and made the ‘right’ decision – “informed compliance” Stapleton et al (2002) in action. Avoiding that process was one of the major reasons why many of the women I cared for chose to birth at home. As I felt it was unethical to revisit that decision unless some new factor arose which required reconsideration of her decision, I could not, and did not, comply. Secondly, I knew Arlene did not make this decision lightly; she embraced the responsibility for that decision in the same way as she made every other decision on nourishing and caring for herself (and, therefore, her baby) in pregnancy. It was made with her baby’s welfare uppermost in her mind. And finally, I had left behind the deference to medical practitioners on non-medical matters when I left hospital employment. I could not defer responsibility for my midwifery practice to a medical practitioner even if I wanted to, which I did not.

So, Arlene’s labour was the catalyst for significant changes in my practice. I became a continuous student of wide-ranging literature, contemplating content and context and incorporating it into my practice when it was appropriate and robustly conducted. This would, at times, give rise to midwifery care that was counter to the care recommended in the local hospital protocols. As a result of this positioning, Arlene’s labour proved to be my first and my last attempt to seek support for myself in orthodox obstetric fora.

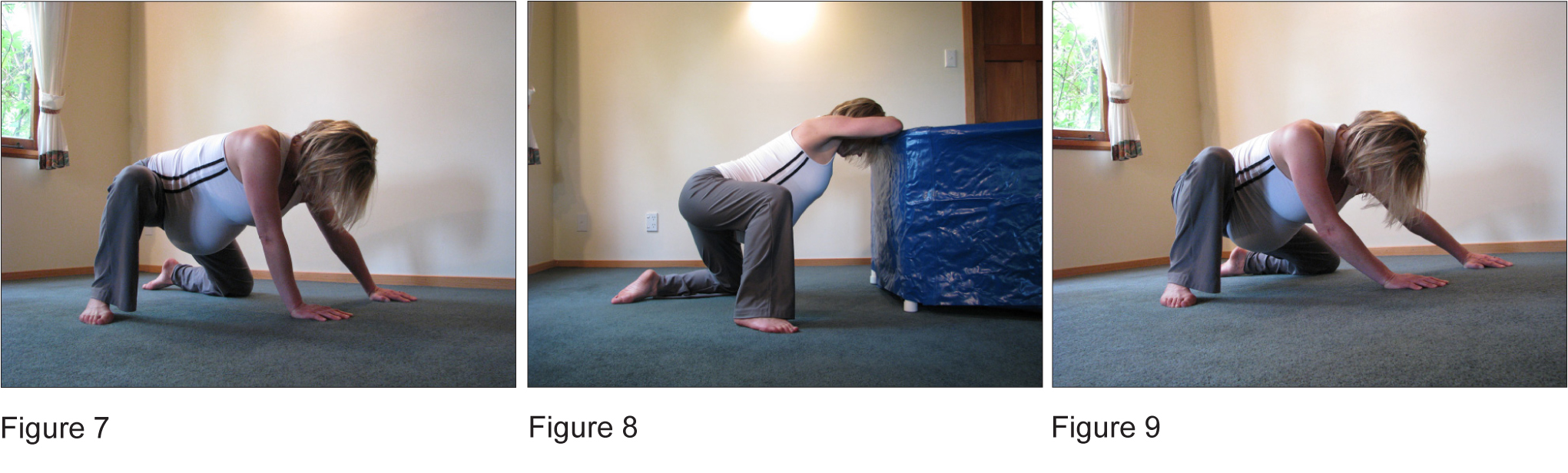

This forward leaning accentuates the spinal curvature and opens the angle of the pelvic brim as the pelvis is tipped forward to enable the baby’s head to enter the pelvis if it has not already done so prior to labour, and enables his shoulders to pass through the pelvic brim.

This forward leaning accentuates the spinal curvature and opens the angle of the pelvic brim as the pelvis is tipped forward to enable the baby’s head to enter the pelvis if it has not already done so prior to labour, and enables his shoulders to pass through the pelvic brim. Women who are working hard to deal with ‘bony’ pain in labour as baby moves through the pelvis, intuitively adopt positions such as the ‘exaggerated runner’s start’ (Figures 7 and 8), leaning one way or the other to increase leverage on the hips (Figure 9) and widen both the mid pelvis and the pubic arch.

Women who are working hard to deal with ‘bony’ pain in labour as baby moves through the pelvis, intuitively adopt positions such as the ‘exaggerated runner’s start’ (Figures 7 and 8), leaning one way or the other to increase leverage on the hips (Figure 9) and widen both the mid pelvis and the pubic arch. Women on the floor do these intuitive movements without consideration of either falling off a bed with their (sometimes) sudden movements, or that they will run out of surface area to place their knees and feet wide apart. The midwife, having witnessed this primal drive to move in labour that non medicated women exhibit, will have no doubt about the inherent dangers of the obstetric bed.

Women on the floor do these intuitive movements without consideration of either falling off a bed with their (sometimes) sudden movements, or that they will run out of surface area to place their knees and feet wide apart. The midwife, having witnessed this primal drive to move in labour that non medicated women exhibit, will have no doubt about the inherent dangers of the obstetric bed.

Having worked with numerous women who have been given this Failure To Progress (FTP) label in their previous birthing, my experience has shown that this abbreviation more often than not actually reflects a caregiver’s Failure To be Patient when the notes are perused. While the permanently scarred uterus that results with caesarean section is lifelong, the emotional scarring of the ‘failure to progress’ label is frequently one that never lets go of the woman until she has experienced birth on her own terms. Nadine’s second birth, a waterbirth at home, was accompanied by a noticeable restoration of her faith in her ability to give birth – faith that had been ruptured by her previous experience. Both these births and the issues that impacted on Nadine’s first labour and birth are addressed in this story.

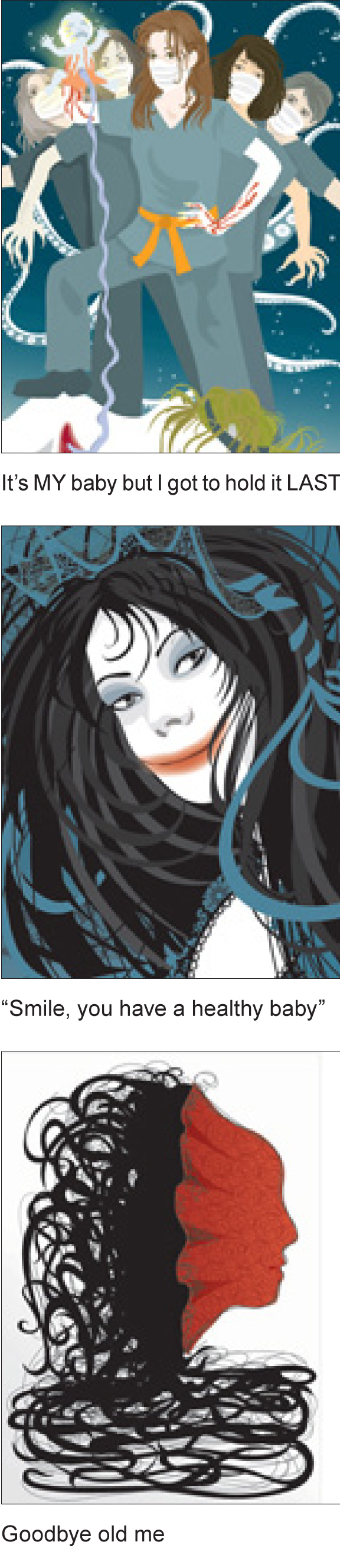

Having worked with numerous women who have been given this Failure To Progress (FTP) label in their previous birthing, my experience has shown that this abbreviation more often than not actually reflects a caregiver’s Failure To be Patient when the notes are perused. While the permanently scarred uterus that results with caesarean section is lifelong, the emotional scarring of the ‘failure to progress’ label is frequently one that never lets go of the woman until she has experienced birth on her own terms. Nadine’s second birth, a waterbirth at home, was accompanied by a noticeable restoration of her faith in her ability to give birth – faith that had been ruptured by her previous experience. Both these births and the issues that impacted on Nadine’s first labour and birth are addressed in this story. She gave birth in the pool and lifted her baby up immediately into her arms with that smile for her baby that only a mother can give – and the little ‘hello’.

She gave birth in the pool and lifted her baby up immediately into her arms with that smile for her baby that only a mother can give – and the little ‘hello’.