This post was originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2009; 1: 13-19. Updated and revised 3 March 2014

Using deep warm baths in labour is a common strategy that many home birth midwives have used for at least three decades in New Zealand to promote relaxation and comfort for labouring women. Such use of water has been recognised as integral to promoting physiological birth, irrespective of whether or not the woman actually plans to birth in the water. In recent years it has become more available to hospital birthing women, with some hospitals having purpose built pools installed.

youtube.com/watch?v=niJ6F2p9Ql8

Waterbirth represents a past and present struggle to practice midwifery in a society that embraces technology and medical interventions throughout the childbearing continuum—a value system which poses threats to the midwifery profession (and childbearing women) in New Zealand in the year 2009.

The first waterbirths in New Zealand

There is little documentary evidence of using water at the time of birth in the traditional practices of Maori in New Zealand. It was common, however, for babies to be born on beaches in the Te Kaha area Binney & Chaplin (2011), Irwin & Ramsden (1995), and Makereti (1986) records the use of water to facilitate birth of the whenua (placenta) when it was delayed.

Estelle Myer

humanitad.org/team/37/

The first of the modern water births, believed to be the first in the Southern Hemisphere, occurred at Estelle Myer’s Rainbow Dolphin Centre in Northland’s Tutukaka, on 17 March 1982. The baby’s mother, Suzanne had read an article on waterbirth in the New Zealand Women’s Weekly nearly two years previously. It described the underwater birth experiments of Igor Charkovsky, the Russian proponent of waterbirth. A second article in the same magazine in late 1981, when Suzanne was again pregnant, affirmed her desire to waterbirth. Though she had not contacted Estelle, Suzanne drove her house bus and three children up to Tutukaka intent on birthing in water. They found Estelle was away in Australia, so they camped out to await her imminent return Anonymous (1982a).

Estelle was not a midwife—the media labelled her ‘an Australian dolphin researcher’ Anonymous (1982a). Having an affinity for dolphins and whales, she reported they would turn up wherever she went in the world.

youtube.com/watch?v=Dh0v1_2JWMY

Such was this affinity, Estelle planned to set up a research programme on waterbirth at National Women’s Hospital based on the work at Pithiviers of well-known doctor, Michel Odent. Estelle has enlisted Michel’s support and, reportedly, he was prepared to come in July 1982 to supervise the start of the programme Anonymous (1982b). It had been planned that a birth would be attended by representatives of National Women’s and Whangarei Hospitals, but that baby was born at exactly nine months—a week earlier than anticipated Anonymous (1982a).

In the meanwhile, Suzanne was attended by Estelle, friends, a midwife and a nurse. Baby Zhan, weighing 3.6 kilogrammes, was born in the bath, in a posterior position—Suzanne’s second persistently posterior baby—after two and a half hours of labour. This much publicised birth caught the imagination of the local people and a Whangarei retailer offered a spa pool for the next waterbirth Anonymous (1982c).

A third waterbirth again made headlines, this time in the Auckland Star, being featured on the front page of its home delivery edition. While the waterbirth was planned to have occurred in Wellington Hospital, the mother-to-be came to Auckland when she was a week ‘overdue’ to farewell her brother overseas. When her labour started, she contacted Estelle whom she had met at a seminar in Wellington. Estelle directed her to an address in Castor Bay where the woman gave birth. There was trauma to her perineal tisues, which was repaired by the attending midwife. The woman was encouraged to rest and recover by the midwife, but she was taken out of the midwife’s care by her mother to a motel, where North Shore Hospital was contacted. She was taken to National Women’s Hospital Anonymous (1982d).

So what do these early waterbirths, that happened nearly 30 years ago, have to do with midwifery in New Zealand then, and now?

The context of the 1980s waterbirths

While ‘being a midwife’ keeps us focused on the individual woman, it does not exist in isolation outside the context of our wider society. It is this context that provides the greatest challenges to maintaining the ‘normality’ of midwifery, and indeed, impacted on the aftermath of the above births.

In the early 1980s, waterbirth focused attention on home birth and the practice of the domiciliary midwives who provided planned home birth services. During this time, the Maternity Services Committee (MSC) of the Board of Health had been reviewing “the problem of domiciliary midwives” Henderson (1980)8 for three years. That ‘problem’ was the rising consumer voices of the women’s health movement that had focused on maternity issues from at least 1974, and the Auckland Home Birth Association, which had established in 1978. The number of home births, rather than disappearing as had been predicted, had been increasing from 1974 onwards Department of Health (1979) when Carolyn Young and Joan Donley, two Auckland domiciliary midwives, had commenced practice.

The New Zealand Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society (NZOGS) was strongly opposed to home birth. In 1977, the Society urged the (then named) Department of Health to explain how it could substantiate payments to domiciliary midwives Bashford (1977). NZOGS knew it could not stop the demand from women for a home birth service, and indeed, any attempt by it to do so would “no doubt stimulate even more vociferous demands” from women. However it knew where it could control the rising home birth numbers and it did so, recommending to the Department of Health that they control the activities of midwives and (general practitioners) who provided the service. This “proper control”, it was proposed, would be best exercised through each local Hospital Board to ensure enforcement of “rigid requirements” McCrostie (1978).

The National Executive of the New Zealand Nurses Association (NZNA) and the Midwives and Obstetric Nurses Special Interest Section of NZNA, complicit in controlling domiciliary midwives, provided the MSC with the format for doing so. It submitted its Policy Statement on Home Confinement in February 1980 Midwives Special Interest Section (1980). This Policy Statement became embedded in The Mother and Baby at Home: The Early Days, which resulted from the MSC review. The report recommended such a degree of ‘proper control’ over domiciliary midwives that an amendment to the Nurses Act 1977 was introduced into Parliament in September 1983. This increased the powers of the Medical Officer of Health so he could suspend a domiciliary midwife from practice for “suspicion of unhygienic practice” (amongst other things). And the example the Department of Health gave?—if she proposed “to deliver a baby in an unhygienic situation, for example, a swimming pool” Department of Health (1983, p. 32).

Waterbirth today

In the intervening years, rather than disappearing, waterbirth has gone from a novel to a firmly established strategy for gentle birth and dealing with tension and pain in labour. Initially it was very embodied in the context of birthing at home where low technology strategies are commonplace.

As the popularity of waterbirth has grown amongst consumers, midwives have increased their awareness of it, some facilitating its growth by incorporating portable birth pools as part of their kit. Waterbirth now no longer needed to be elaborately planned by having expensive pools constructed where no suitable tub already existed. In recent years it has also become available in hospital settings as many have pools available in the labour wards.

To date, no comprehensive national data is available as to waterbirth rates, and how women and midwives utilise pools and baths during birthing. The Midwifery and Maternity Providers Organisation MMPO (2013) reported on 51.9% (n=32,083) of births registered in New Zealand in 2011 from the pool of 61,823 babies born (live and stillborn) during 2011 (p. 9). It recorded a 28.2% use of water for the relief of labour pain and a 7.1% waterbirth rate (p. 36) in the practices of its 866 LMC midwife members (p. 9). Individual practice or facility audits report a 65–75 percent pool use in labour Banks (1998); Cassie (2002) and between 25% Fenton (2002) and 38% Banks (1998) actual waterbirth rates.

The relationship between the rate of waterbirth and the place of birth is significant—the higher the level of obstetric specialist presence, the lower the rate of waterbirth. In the above mentioned MMPO reporting, waterbirth occurred for 21.9% of babies born at home, 21.2% of those born in primary care facilities, 4.8% in secondary care hospitals, and 2.3% in tertiary care hospitals MMPO (2013, p. 36).

The influence of the obstetric environment is not mitigated even when there appears to be tacit support for waterbirth, as in Denmark, for example. Some obstetric hospitals there have an ‘official waterbirth programme’ but only between 0.03% and 3.5% of babies are born in water in these hospitals compared to 4.0%–35.0% of births at home or in small maternity facilities Uller, in Lawrence Beech (1996, pp. 119-129).

What is clear from anecdote in this country is that where hospital ‘authorities’ do not condone waterbirth, or downplay its existence in their facilities ADHB (2011), it does still occur, sometimes under the guise of ‘hydrotherapy’, with interested midwives sometimes acting as self-appointed data collectors.

The context of waterbirth today

What has remained similar today to the maternity services of the 1980s is the culture of an illness model of childbirth, which embraces obstetric hospitals as appropriate environments to celebrate the birth of a baby. Once in labour, the majority of women in New Zealand move from their familiar homes into these (often) unknown environments where the nature of the childbirth continuum is not recognised.

Labour is treated as a distinctly separate entity – a health crisis, which, as a medical model of birth would have us believe, requires a different set of beliefs and behaviours. This is illustrated in the philosophical shift that occurs with the use of drugs in labour. Women, urged to avoid all social and recreational drugs during pregnancy, receive in labour unknown quantities of nitrous oxide and narcotics, along with at least 24.9 uses of epidural anaesthesia per 100 births (excluding the 23.6% of babies born by caesarean section) MOH (2012). It is as if the potential harm of drug use that exists in pregnancy suddenly dematerialises in labour, some intrinsic factor protecting the woman and her unborn baby. Yet epidurals are known to increase instrumental births and caesarean section for foetal distress, cause fever and urinary retention, and aspects of opioid use remain unstudied. As Jones et al (2012) summarised in their overview of systematic reviews:

despite concerns for 30 years or more about the effects of maternal opioid administration during labour on subsequent neonatal behaviour and its influence on breastfeeding, only two out of 57 trials of opioids reported breastfeeding as an outcome.

Implicit in obstetric hospitals is the dominance of medicine (obstetrics, and in recent years, paediatrics). This dominance is maintained by a society which accepted introduction of invasive and inappropriate technologies into routine obstetric practice without adequate testing, and which accepts continued use, despite well known detrimental effects, as exemplified by Electronic Foetal Monitoring. It is also this same society which fails to see the paradox in medicine’s demand for “more evidence on safety of waterbirth before it is offered routinely” Nguyen et al (2002).

Clinical guidelines

Obstetric hospitals cater for large numbers of women and various disciplines of caregivers. Order and control of resources (equipment, staff and the facility) are maintained through Policies, Protocols and Clinical Guidelines (the latter subsequently referred to as Guidelines). These are imbedded in the strategy of ‘risk management’ of each institution.

The professed purpose of a Guideline is to indicate professional health care that would be appropriate to consider in a particular circumstance. The degree of ‘guidance’, as well as the care that is recommended for any particular situation, varies throughout New Zealand as hospital Guidelines are locally determined. It is these documents that declare the philosophical underpinnings of birth in hospitals – both as to what care is available, and ‘the way we do it here’. They usually reflect locally determined obstetric practices rather than evidence-informed midwifery practice and, therefore, lack understanding of how to nurture physiological birth.

Two aspects of this guiding of care during pool use in labour are discussed below. These are the ways in which Guidelines can define ‘normal’ labour care and their ability to create pathology.

1. Clinical guidelines as an agent to define ‘normal’ labour options

Exclusion criteria for pool use in labour are often foetocentric and are frequently without any evidence-informed rationale for exclusion, for example, prolonged rupture of membranes. These criteria deny well women the known physical support of water immersion, valuable in a twin pregnancy, as well as the comfort producing qualities for all women, including those with breech presenting babies or where babies are ‘too large’ or ‘too small’, as well as those labouring after previous caesarean section.

If Guidelines are interpreted as prescriptive of care, they are a very effective tool to rigidly control practitioners (midwives) and women. This interpretation is evident when women and midwives are heard to say ‘I had to …’ or ‘I was not allowed to …’. The informed decision-making process is negated as care is seen to be mandatory and unable to be declined or omitted. Care becomes unresponsive to the needs of the individual woman, effectively controlling her and her birthing experiences and, if based on obstetric practices, transforms midwifery practice into a medical model of care. Thus midwives must recognise the potential that Guidelines steer them away from providing individualised care if they have an uncritical acceptance of them.

Many midwives cite the unwritten power of Guidelines as the reason they embrace them. As I have previously written:

It is common to hear ‘Guidelines are for the consideration of the wise and the adherence of fools.’ This innocuous representation does not hold true to midwifery experience. A great deal of power is given to Guidelines in case and practice reviews, auditing and disciplinary proceedings. This impacts on how far a midwife can ‘stray’ from the dominant medicalised culture of birth Banks (2001, p. 35).

2. Clinical guidelines as a pathologising agent

The unborn baby is dependant on his mother for effective heat dispersal. The woman must therefore be surrounded by a comfortable temperature or be able to sweat if she needs cooling. If deeply immersed in overheated water, she will be unable to disperse heat because the mechanism for efficient heat loss for her, and therefore her baby, is overridden.

madeinwater.co.uk/birth-pool-thermometer/

Tachycardia in unborn babies has been created by adherence to a Guideline which defined optimal water temperatures as 37°C–38°C. Since the mid 1990s, a new optimal water temperature, between 36°C–37°C Deans & Steer (1995), has been commonly adopted in hospitals. Like its predecessor, it disregards the fundamental problem that there is no optimal water temperature for all labouring women. It must be individually determined, and is dependant on many variables, for example, the woman’s circulation, metabolism and adipose tissue covering. Meanwhile, the tachycardia of the unborn baby of an overheated woman can lead to a diagnosis of ‘foetal distress’, which precipitates the Cascade of Intervention that may ultimately lead to caesarean section.

Guidelines are written for the care of the masses and do not acknowledge individual difference. When a Guideline is applied prescriptively, it has the potential to become a pathologising agent in an otherwise well-woman experience. Such pathology has occurred when a guiding optimal water temperature has been prescriptively applied.

Keeping midwifery ‘normal’

Midwifery, by its very with-woman definition, determines our position for treating each woman as an individual, with each of her childbirth experiences also being individual. Within this, pregnancy, labour and birth, and mothering merge one into the other, despite such things that divide the continuum into modules (for example, payment structures) and into discrete phases (for example, medicine’s stages of labour).

A tension exists in providing a well-woman service to women in labour in a practice setting that anticipates pathology in birthing. To be able to keep the practice of midwifery ‘normal’ in obstetric hospitals, the midwife needs to continue providing care that is woman-centred, rather than institution-centred. This requires her to consider the validity of each individual Guideline as they apply to the individual woman. Her questioning will lead her to ask:

- Is this Guideline evidenced-informed?

- Which discipline’s evidence informs it?

- Does it include midwifery evidence?

- Does it promote ‘best practice’?

- Does it promote and protect the potential for physiological birth?

- Will it activate a Cascade of unnecessary Intervention?

- Is it appropriate for this individual woman?

Consideration of these issues aids the midwife’s discussion with the woman so the latter can make an informed decision, and therefore, give or withhold her informed consent to the care specified in the Guideline.

A Guideline may also embrace an illness-orientated task that is incongruent with caring for well-women. One such practice is the routine taking of all women’s temperatures in physiological labour. Whether it is Guideline-driven or has simply been rolled over from a task of nursing, the value of its routine use in well-woman, non-intervened-with labour and birth care is, at best, dubious.

To suggest that we extol a woman to check her temperature or that of her bath with a thermometer throughout pregnancy would raise a smile. Common sense tells us that we do not take our temperatures in the absence of illness and that we feel the warmth of water with our hands. Yet this common sense appears to leave the hospital labour scene, as all women, rather than just those exposed to invasive technologies, become subject to temperature taking—their own and that of their pool water.

While at first glance it may appear to be insignificant as to whether or not a thermometer is used to establish water temperature, it is argued here that it is the seemingly insignificant and the minutely small ‘tasks’ that midwives do that embody what we believe about birth. The above strategy adapts the medicalised belief of ‘no birth is normal except in hindsight’ to ‘no woman is well except in hindsight’. It exhibits the same incongruous behavioural state of compartmentalising labour as a separate entity within the childbearing cycle. It also insidiously undermines women’s (woman’s and midwife’s) own ways of knowing and common sense. Thermometers can be viewed as a ritual tool to create pathology by way of tight boundaries of what is ‘normal’, in the same way as routine vaginal examinations created the tight boundaries of what is considered ‘normal’ cervical dilation or progress. These tight boundaries precipitate intervention as any ‘aberration’ is seen as needing correction, while the act itself is not considered as potentially disturbing the altered headspace (and therefore, the physiology) of the birthing woman.

Within our professional body, the New Zealand College of Midwives (NZCOM), we need to be aware that Consensus Statements, while using a different process for development, can be equally erosive of individualised midwifery care, and simply mimic Guidelines. NZCOM’s Consensus Statement, The Use of Water in Labour and Birth NZCOM (2002),has turned the very ‘ordinariness’ of soaking in warm water into a complex issue. It states a need for “careful documentation … of maternal and water temperatures … and the approximate surface area of the woman’s body submerged” (p. 1). While maternal and water temperatures can easily be assessed without a thermometer, the intention is that one should be used as evidenced by suggesting that a woman’s temperature needs to be lowered if it rises above 1°C of her baseline. It would be interesting to know at what point(s) one records the degree of skin submersion of the ever-changing surface area of a labouring woman in motion.

It is important to recognise that such a specific Consensus Statement can be used against midwives in the same manner as Guidelines are currently used. While purporting to be evidence-based, that evidence reflects the environment of the studied (hospitals) where “thermozeal” Anderson (2004), the propensity to test water temperature, is prevalent in the midwife(ly) tasks during waterbirthing. This activity, however, is not a feature of waterbirthing at home, where unnecessary disturbance to labour is minimised. Gauging water temperature is done with the hand, while the woman’s temperature is assessed by means which include touch, pulse rate, skin colour and eye brightness. The knowledge that body temperature is equally affected by factors such as hydration, energy levels, strength of labour, and diurnal and nocturnal body rhythms, is also utilised. These are effective assessment strategies as shown by the lack of babies who experience problems with tachycardia, as well as the lack of labouring women who are overheated. Thus, midwives practising in the woman’s home are unlikely to adopt other than their usual practices, which may leave them vulnerable to censure because of a Consensus Statement which is inappropriate to all practice settings.

The challenge for midwifery today, with most power given to the medical hierarchy of evidence in punitive forums and obstetric environments, is to (continue to) value the midwifery knowledge which is gained when women experience non-interventionist birthing. Anecdotal experience indicates that as midwives are directed to change practices by investigatory bodies, they can be ‘forced’ to deny the midwifery knowledge developed by attending women in physiological birthing – its difference unacceptable in forums using obstetric knowledge of intervention-laden, managed birth as the benchmark.

In recent years, many midwives have responded to the challenges to ‘prove the safety’ of using water in labour by auditing, testing and measuring many aspects of the experience. It could be argued that these strategies are evidence-gathering exercises that are used to silence critics and, therefore, ensure availability of waterbirth in hostile environments. While we cannot control those professions that continue to behave as if midwifery was a subordinate profession, midwives can determine their own research agenda and the manner in which they undertake midwifery enquiry. It should be recognised that attempts to appease critics may focus on a medicalised experience if research questions and study protocols anchor the enquiry to the typical, medically-managed birth. It will not give a picture of how women use water during physiological birth unless physiological birth is the benchmark. Equally, if auditing is pre-dominantly used as a tool to assess and ensure Guideline compliance then it will not increase midwifery knowledge about ‘what happens during the use of water in physiological labour’.

Conclusion

In 1998, I reviewed the last 100 births in my home birth practice to gauge the level of pool use. A birth pool was made available to 98 women, of which 79 chose to use this availability. In labour, 65 actually used the pool and 38 women birthed in it. Those who did not end up using the pool either birthed before it was ready or were not drawn to water in labour Banks (1998). The temperatures of both the water and the women were assessed in the manner usual for home birthing, and no woman was overheated, nor did any baby experience tachycardia.

If the experiences of women are not manipulated by the caregiver’s non-critical compliance with Guidelines, and women are left to determine the most comfortable water temperature for themselves, the water temperature range is 28°C–38°C, with most choosing water between 28°C–32°C prior to birth Muscat, in Lawrence Beech (1996, pp. 77-81), findings which others are also observing Geissbuehler et al (2002). Equally, when women are free to use a birth pool as they wish, the majority will do so before they are five centimetres dilated and most will go on to birth in the pool or get out when in advanced labour Haddad, in Lawrence Beech (1996, pp. 96-108).

Over one hundred years on from midwifery registration, the threat to physiological birth is more present than ever. While our society may appear to value intervention and technology in childbirth, the tenet to midwifery practice has remained unchanged—midwifery is about supporting women in the natural birthing process in the absence of problems. While birthing at home moderates (if not negates) challenges to the autonomy of woman and midwife, the ‘authority’ to dominate over women and midwives, is potently present in obstetric hospitals. It should be recognised that, while midwifery practice is affected if the midwife assumes a subordinate role, no such authority to control midwives has been given to medicine by the women of New Zealand. The midwife has been given a social (and legal) mandate to practice autonomously, ensuring she is not a sub-ordinate practitioner who defers to self-promoting medical authority. To ensure that the midwife’s autonomy is effective, she must resist embracing mechanisms that change her care from woman-centred to hospital-centred care. This can only be done by critical consideration of Guidelines as to their evidence-informed foundation. If they prove to be so, then well and good. If not, then the midwife is duty bound to inform the woman that the Guideline is not evidence-informed, and therefore, inappropriate midwifery care.

The first midwife of the 1980s paid dearly for supporting women who chose waterbirth. She was dismissed from her employment at Dargaville Hospital Dominigue (1982) and paid the ultimate price for a midwife – her name was taken off the Register Donley (1986, p. 106). While devastating in its timing, as discussed previously, the gift this midwife gave to women and midwifery was the pioneering of an option which is cherished by those of us who support women to waterbirth. This unnamed midwife needs to be honoured for that pioneering, which promoted physiological birth, despite the significant consequences of censure and persecution from those who felt threatened by her strong, focused midwifery spirit. In her wake, other midwives, also exhibiting that same determination to practice woman-centred midwifery in a medicalised world, have ensured that immersion in warm water during labour and waterbirth have become tangible realities for what must be thousands of women and babies in New Zealand in the years that have followed.

theshiftofconsciousness.info/dolphin.html

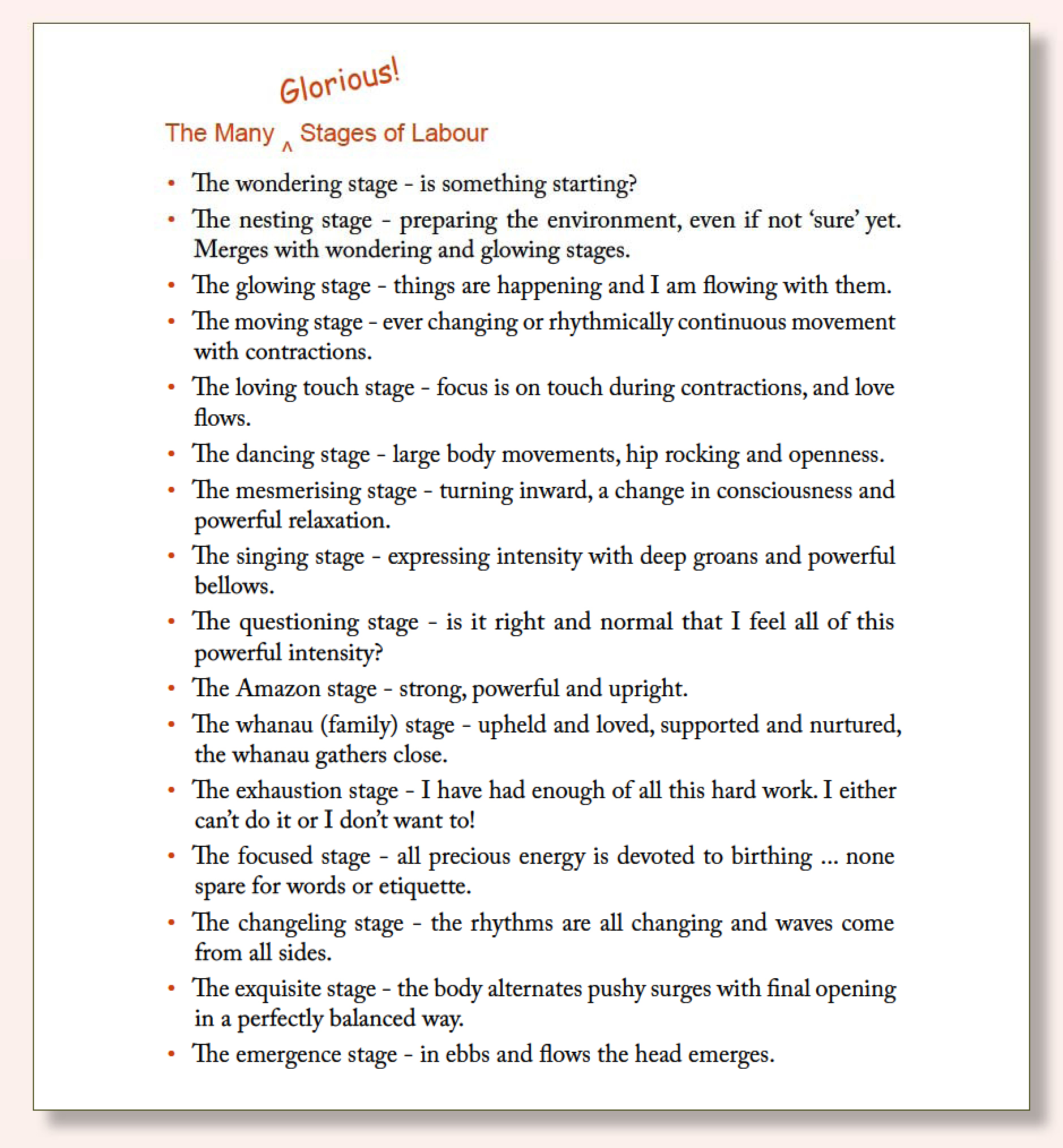

That night I presented them to her, and she loved them. There were so many to choose from! She could try out a new one every hour, or more! In particular, though, she noticed that these were things she could do, so that the stages of labour became not just something ‘nature’ or obstetrics imposed upon her, but something she could be an active part of.

That night I presented them to her, and she loved them. There were so many to choose from! She could try out a new one every hour, or more! In particular, though, she noticed that these were things she could do, so that the stages of labour became not just something ‘nature’ or obstetrics imposed upon her, but something she could be an active part of.