In this post, originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2010; 5: 19-22, Avon Lookmire, now a registered midwife, discusses how the current ‘stages of labour’ do not reflect women’s experiences of labour, and she shares her ideas of how the process may be reframed.

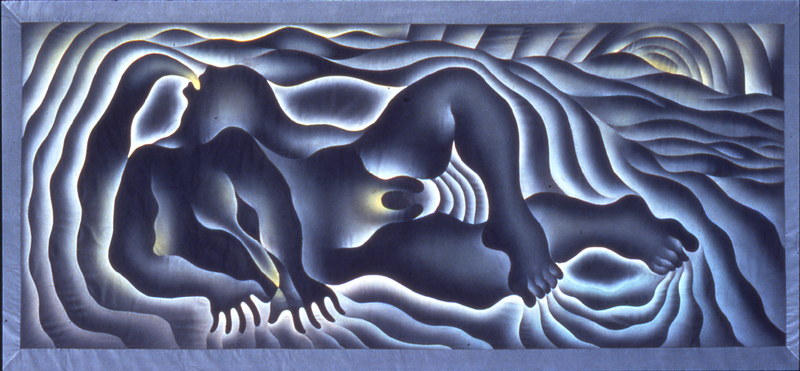

Earth birth, by Judy Chicago. 1983

http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/archive/images/376.1559.jpg

Midwifery knowledge comes from many places, but often the most valuable knowledge comes directly from birthing women. As a student midwife, I am lucky enough to have a sister, hapu (pregnant) with her second baby, who challenges my midwifery knowledge and keeps me honest and woman-centred.

Like me, my sister Leith is a compulsive writer, and recently presented me with the first draft of her “birth musings” (a nice variation on a ‘birth plan’). From among the many pages, one part in particular stuck with me: she described how during her first birth, the model of ‘the three stages of labour’ disempowered her immensely, and disregarded her long and arduous journey. She wrote:

I think I really wanted to be told I was amazing and that my labour was progressing super well. The language around birth is enormously unhelpful here. It’s not easy to celebrate progress and ‘go with’ the process of birth when you’re defined as ‘at the start’ for hours and hours (“first stage”). I didn’t realise at the time, but one of the biggest messages I got from my preparation for Juna’s birth was that I was aiming for 10cm dilation and nothing important or interesting would happen until then. In that context, examinations to estimate dilation are almost inevitably disheartening … Perhaps I’d like to re-language this birth, with a more sensible range of stages to reflect the work I am doing birthing my baby … Perhaps Avon and I can break labour down into a dozen or so meaningful stages with images to help me visualise these and work with my body?

Meaningful stages of labour? I had never before considered it, but she had a good point. Still, consumed by midwifery study and practice, I filed this challenge away for a less busy time. Soon after, however, I was dutifully working my way through the ‘learning outcomes’ of Biosciences for Midwifery when I was confronted with the question “Define the three stages of labour”. It seemed like fate. Were there really concrete stages of labour that could be defined?

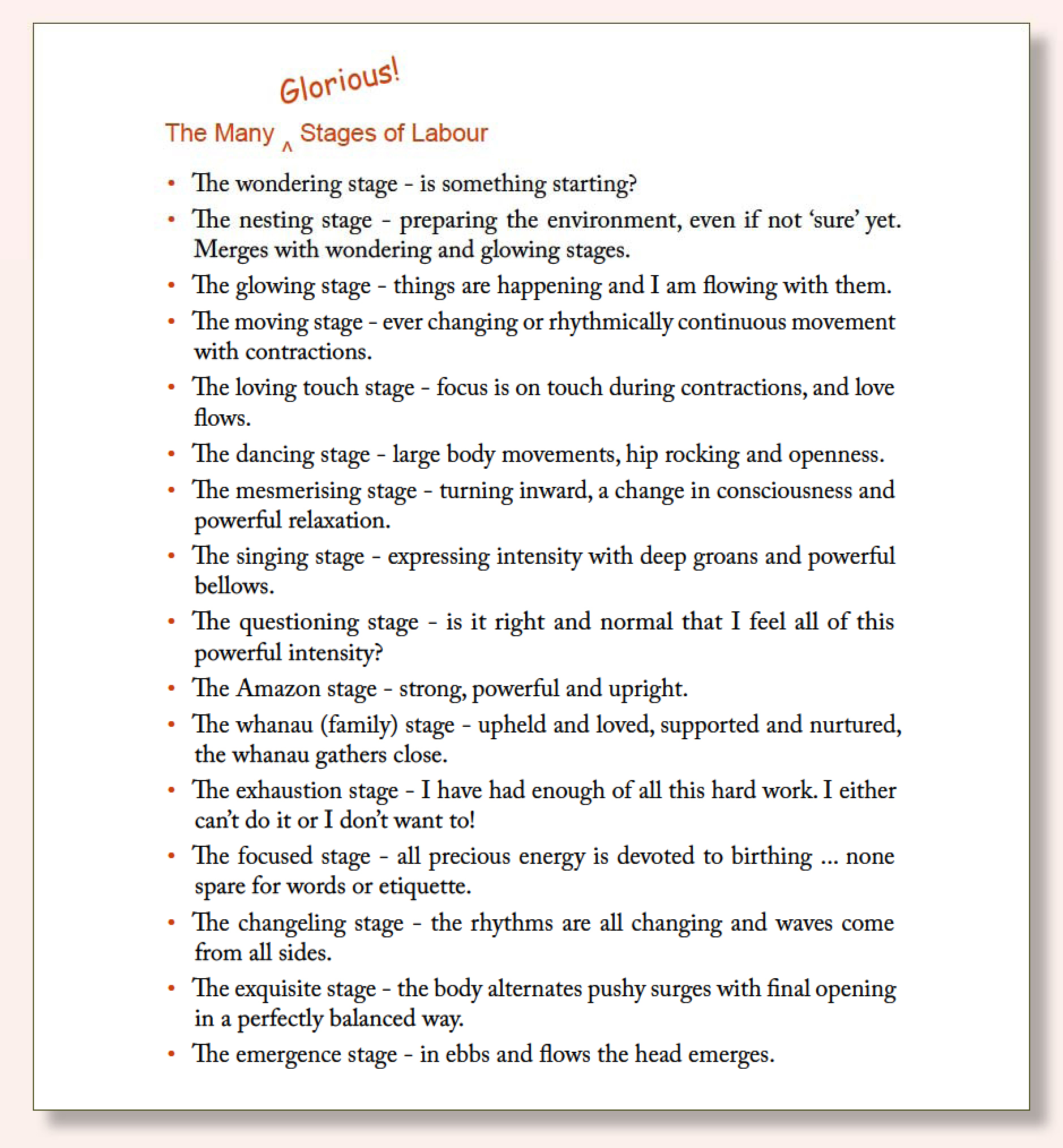

I started reading through the relevant section of my textbook, but Leith’s challenge was pulling at me. I paused and pulled out a scrap of paper and idly wrote along the top ‘The Many Stages of Labour’.

Still half pretending to read the required section, I started to jot down all the stages of labour that are not given names or status within midwifery. They came surprisingly thick and fast, so obvious yet so unspoken. After adding a number of stages I returned to the title and used a little arrow to add another word, so that it read: The Many (Glorious!) Stages of Labour.

That night I presented them to her, and she loved them. There were so many to choose from! She could try out a new one every hour, or more! In particular, though, she noticed that these were things she could do, so that the stages of labour became not just something ‘nature’ or obstetrics imposed upon her, but something she could be an active part of.

That night I presented them to her, and she loved them. There were so many to choose from! She could try out a new one every hour, or more! In particular, though, she noticed that these were things she could do, so that the stages of labour became not just something ‘nature’ or obstetrics imposed upon her, but something she could be an active part of.

The three stages of labour seem to be one of those pieces of midwifery knowledge that remain central to the way we talk about birth, despite having limited usefulness or validity. Other contributors to this journal have pointed out, for example, the inaccuracy of recording ‘full dilation’ or ‘beginning of second stage’ based on when the midwife performed a vaginal examination rather than when a real change in stage took place within the woman Wickham (2009). Similarly, Walsh (2007, p. 35) argues that “the division of the first stage of labour into latent and active is clinician-based and not necessarily resonant with the lived experience of labour”.

So one has to ask: why would we come up with a system of describing labour that does not accurately portray what is really taking place? Furthermore, if the three stages model of labour is “clinician-based”, is it actually useful to clinicians such as midwives in practice?

It seems that the ‘three stages’ model of labour has its roots in the mid-twentieth century when the ‘active management’ of childbirth became commonplace in hospitals Banks (2000, p. 39). In order to apply the strict time limits that were deemed to characterise ‘normal’ labour, discrete beginning and endpoints were needed, and hence labour was “compartmentalised” into stages Banks (2000, p. 39).

Many aspects of the ‘active management’ of labour have been challenged, for example, breaking of the amniotic waters removes an important protection mechanism for the baby from intense contractions, and increases the risk of infection, particularly in combination with frequent vaginal examinations Romano & Lothian (2008); Dixon (2003). The practice of defining the second stage by cervical dilation so that the midwife can direct the woman to push, while simultaneously limiting the time for which she will be ‘allowed’ to do so, has been critiqued by many authors Wickham (2009); Sutton (2000); Walsh (2000), yet this is the essence of the three stages model of birth. While it gives the impression of objectivity and order, it is really highly subjective, even manipulative.

The three stages model of birth has its foundation in the belief that the expert knows best. Thus, as Leith noted:

Pregnant women are led to doubt their right to say when they are ‘in labour’. There doesn’t seem to be any clear-cut definition, and women are gently mocked by health professionals and loved ones if they are brave or foolish enough to make the judgement themselves.

Walsh describes this phenomenon as a way in which midwives balance what women tell them against what is expected and acceptable within the obstetric model of birth Walsh (2007, p. 35). To put this more bluntly, midwives ignore or misrepresent women’s descriptions of labour so that their labours can be fitted into a pre-defined model, which is then further reinforced as being ‘normal’! Miller (2009).

It seems hard to imagine any benefit of this system to birthing women, whose lived experiences are swept aside and replaced by ‘expert’ measurements of what ‘really happened’. Furthermore, the three stages of labour seem to have little practical use to midwives unless they are following a strict ‘active management’ approach to labour. Indeed, it appears that significant effort may be expended by midwives in their attempts to fit all births into an acceptable obstetric box.

Therefore, this alternative set of stages is presented, not as a definitive list, but as a starting point for a change in consciousness regarding labour progress. As Leith so eloquently described, the stages we use to describe labour should be meaningful, and should reflect their power, their intensity, and their challenge. There is so much scope for detail and meaning when describing the life-changing process of birth, surely we can do better than ‘one, two, three’!

In conclusion, as a home birth mother-of-two and student midwife, I do feel that my perspective shifts and alters as I learn new things and adopt a midwife’s point of view. This is inevitable – perhaps essential – but also limiting if there is not a corresponding pull towards a birthing point of view providing a healthy counter-tension. I am so grateful to Leith for giving me this new perspective on the stages of labour, and for reminding me about the importance of words.

This post written by Australian home birth midwife Sue Cookson (RM) was originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2010; 6: 65-67. Updated 30/12/15.

Thirty-one years ago on a hot December morning I gave birth to my second daughter. It was a rather unusual birth which began with membranes rupturing and a foot entering my vagina. Within an hour, two blue feet were at my vaginal opening where they stayed for a further two hours before she made her appearance. Contractions were regular but mild with the baby periodically retracting one foot and kicking off against my vaginal wall. Then, when in her ‘perfect position’, she descended. The descent took seven minutes from the umbilicus to the completed birth of the head. The birth was a pain free experience except for the uncomfortable extraction of both her arms by my doctor, as shown in the photograph below. It has taken me 26 years to understand the reason for that minor assistance with my birth.

I have been attending homebirths in Australia for 28 years but breech births did not really come my way until recently. I have supported a few women over the years to birth breech babies vaginally in hospitals, have had one undiagnosed homebirth breech in my practice, and attended two other homebirth breeches as second midwife. They were all good breech births. In 2009 I was involved in the launch of the DVD ‘A Breech in the System’ which documents a woman’s journey to give birth vaginally to a breech baby in an Australian hospital, where I was the supporting midwife.

Last year also brought me the stories of five breech deaths, with the babies being born in different settings across three different countries. These babies were all alive during the process of birth but once born, breathing was not established. From the umbilicus to the birth of the head, these babies took 13, 13, 15, 17 and 19 minutes.

The stories of these breech deaths really concerned me. It raised the fear of breech birth, which for me was – ‘what would I do if I couldn’t assist the baby through alive and well and, even though I had birthed my own breech baby vaginally, did I have the knowledge and skills to deal with the ‘unknown’ of breech birth?’ I decided to explore the teachings around breech birth and ask some experienced practitioners for their wisdom.

I began by contacting Maggie Banks, midwife from New Zealand and author of Breech Birth Woman Wise, and Andrew Bisits, obstetrician from Newcastle, Australia who has specialised in vaginal breech births for the past decade. I also consulted texts by Anne Frye 1 and Bruce T. Mayes 2. My questions were:

- What constitutes need for intervention in a breech birth;

- Is there a specific time limit for breech birth from the umbilicus to the completed head birth; and,

- What is the management to encourage descent and delivery of the breech baby if needed?

Frye’s extensive text examines the question of timing and she states, “both the medical and midwifery literature are rather spotty when it comes to the all important question of the timing…[from the birth of the umbilicus to the birth of the head]”.3 She cites well-known references which nominate a range from 3-5 minutes to 5-10 minutes to “the parameter rests entirely upon the condition of the baby”.4 Mayes, however, declares that 20 minutes may be a safe limit although most babies will be born within 10 minutes.5

This is all rather confusing. Is it three minutes, or 10, or 20? My initial training with John Stevenson suggested 5-10 minutes if the baby was previously uncompromised, so respecting a time frame similar to shoulder dystocia. But what does ‘rests entirely on the condition of the baby’ mean? So the baby is born to the umbilicus, the heart rate is less than 80 beats per minute, colour is pale but pink, baby cycles so has tone and reflexes, how long do we have? One midwife who lost a baby, said the baby was alive and cycling two minutes prior to its birth (and death), another said she knew the birth was ‘taking too long’ and the baby died prior to the shoulders presenting. How quickly can a baby move into a comatose state and not recover, or were these births true stillbirths?

Communication with Maggie Banks about my queries brought me back to true midwifery mode; if descent is slow at any time either during the body’s descent or the head birth “change the mother’s position”. Of course, just like we would for a shoulder dystocia! I could feel my head and heart accepting the simplicity of her answer. And the reflection by Maggie on the time frame – “maybe 10 minutes, but definitely led by baby’s condition”.

Andrew Bisits’ response; only intervene in a breech birth “if the baby is bradychardic leading up to the birth of the backside and body; if there are clear delays with the delivery of the shoulders or the descent of the body”, “time from umbilicus to head should be no more than five minutes, absolute maximum of 10 minutes” and to encourage progress “our most overlooked ally with these births is effective suprapubic pressure; it is the most effective surrogate for a contraction”. And so these comments provided me with clear parameters and a different management for the head birth if required.

As happens, I have attended six vaginal breech births in the past six months – six in 26 years, then six in six months! One of these included a very precipitous birth where I was called when the membranes ruptured after an irregular early labour followed by three strong contractions. I was called again eight minutes later and told the feet were born. I stayed on my mobile and drove the seven minutes to the birth to find an arm arrested behind the baby’s head and inhibiting descent. There had been perhaps two contractions in this position and, by the time I was in the house and assisted the arm through, which was really tight and difficult, it had been possibly 10 – 11 minutes from umbilicus to head birth. That baby was deeply shocked, was resuscitated and had a first breath at five minutes. She was breathing regularly by 10, with Apgars of 2, 4 and 5 at 1, 5 and 10 minutes respectively, and was transferred by ambulance. She was in a coma for 50 minutes, but then recovered fully with no expected ongoing morbidity.

Another breech baby was born on the floor of a hospital with the obstetrician on his knees. The woman was in a knee-chest position for most of the descent, then moved her torso to be more upright for the actual birth. The baby came through to the neck in about four minutes then we waited ‘for the next contraction’. When I quietly reminded the obstetrician that there may not be another contraction and the mother could simply ‘let her baby out’, he replied that he wanted to wait until the next contraction. The baby’s colour was going off and her tone dropped so I leant forward and asked the woman to ‘release’ her baby, which she did. The baby was moderately shocked and the obstetrician wanted to cut the umbilical cord and remove the baby for resuscitation. The woman refused to allow him to cut the cord but scooped up her newborn and carried her to the trolley, cord attached!

The next breech was in the shower in a hospital, a 36-weeker. He was a complete breech that converted to a double footling breech. He came through from umbilicus to underarms in about five minutes but then hung with his right shoulder visible but no arm presented. It was the end of a contraction – should I wait for another or should I release that arm? I chose to release the arm, thinking of the time frame already used, making the decision to decrease the possibility of taking ‘too long’. The left shoulder then presented and at the end of that next contraction there was still no arm, so I assisted that through as well. The head came through with a ‘release’ by the mother, so the birth was completed in 8-9 minutes from umbilicus, and the baby had Apgars of 9 and 10.

My most recent homebirth, another undiagnosed breech, was a second baby. This labour and birth was very intense compared with the woman’s first birth, and due to the intensity I asked her to do some asynclitic moves to try to bring the baby down (still expecting a vertex baby and assuming the baby was stuck at the brim). She ended up on hands and knees with her left leg extended, which afforded good progress. The baby was a frank breech and this position gave him the room he needed to move into the pelvis. He descended, rotated on the perineum and then came flying through in about one minute – my job then became to slow his head birth as much as I could.

And so my recent birth experiences which followed my desire to gain more knowledge and so reduce my fear around vaginal breech, have given me the answer about my own breech birth. Did my doctor need to extract her arms? I know that he did what he believed that he needed to do. She was moderately shocked at birth and needed some resuscitation. I am very thankful that I did not have a more compromised baby and did not have to undergo transfer or special care procedures.

Importantly, my belief that breech birth is a ‘variation of normal’ has been fully supported. I now feel confident in understanding both normal progress in breech births as well as the management of difficulties in breech births. As a midwife I have no doubt that we need to be as hands off as practical, but I am a firm believer that we need to have our ‘hands ready’, together with our knowledge, skills and intuition, to assist a breech baby through in its perfectly good time.

References

1. Frye A. Holistic midwifery, volume II, care during labour and birth. Labrys Press: Oregon, 2004.

2. Mayes BT. A textbook of obstetrics. Australasian Publishing Company: Sydney, 1950.

3. Frye A. Op cit; p. 946.

4. Ibid; pp. 946-947.

5. Mayes BT. Op cit; p. 568.

You may also be interested in

Breech Birth Online Workshop

Breech presentation is the 4th most commonly reported indication for caesarean section, and previous caesarean section the first. Breech presentation can be seen…read more

Breech presentation is the 4th most commonly reported indication for caesarean section, and previous caesarean section the first. Breech presentation can be seen…read more

This post written by Cecil Tamang (RM, BM) was originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2010; 2: 40-42.

I once ran across a greeting card which sums up my thoughts about the confirmation of pregnancy. On the front was a picture of a baby and the words “the world’s first 100% accurate greeting card pregnancy test”. Inside was written, “Step 1: Pee on this card. Step 2: Throw this card away. Step 3: Wait for 9 months. If you have given birth, you were pregnant.” While the instant and highly accurate results of technological pregnancy confirmation are undoubtedly useful in some situations, I feel that the elements of uncertainty and time inherent in an inner ‘knowing’ of pregnancy may play an essential role in the process of becoming a mother. Much has been written about the use of technology to offer screening and diagnostic testing in pregnancy, and where women’s knowledge of their bodies and their babies stands in relation to this external voice. The widespread use of technological pregnancy confirmation is inseparable from the greater epidemic of technological testing in pregnancy. I wish to raise the possibility that exclusive reliance on such technological ‘knowing’ may limit our opportunity to engage in the inner process of change and growth that is part of becoming a mother. I explore these ideas within the context of my own experience as a mother, through issues that arose during my two pregnancies. What follows is therefore to be received as one woman’s story; I have undertaken no research to gauge the attitudes of other women on this subject, nor am I privy to the dynamics which underlie their attitudes or motivate their actions.

My daughter was conceived with intention during the first month of inviting a child to our family. I knew I was pregnant when I missed my period. A few weeks into the pregnancy my partner went overseas for several months. Shortly after he left, when I was about six weeks pregnant, I began to have spots of bleeding. Sometimes the blood was bright red, sometimes brown. It was never much, just enough to require a pad.

I felt shattered. My dreams seemed to be dissolving, and I found myself nearly overcome with sadness and self-pity. Being a conscientious student midwife, I immediately went to my textbooks and ascertained that I was experiencing what could be classified as a ‘threatened miscarriage’. I was aware that I could approach a midwife or GP to check the levels of my pregnancy hormones, or even to arrange to view the baby by ultrasound scan. I had the possibility of ‘knowing’ whether my baby was alive or dead, but I felt unequal to facing that knowledge. Firstly, even if tests were to reassure me that my child appeared to be thriving, they would not necessarily be able to explain my bleeding, or guarantee the healthy continuation of my pregnancy. On the other hand, if testing were to confirm that my child was in fact dead, and my body was simply taking its time to pass the little body and tissues, I thought my heart would break. Without the support of my partner, I felt vulnerable to the harshness and inevitability of such a diagnosis, and chose not to pursue any testing. In choosing not to try to ‘know’, I found gentleness in uncertainty. Hope and despair could co-exist side by side. On the days when the bleeding was brown, I felt buoyed by hope that my child was healthy. When the spotting returned to red, I would become sobered again with the possibility that she was dying or dead.

I slowly moved away from seeing this as my journey alone; it was the destruction of my dreams of motherhood that were causing me the most pain. For my child, the stakes were higher: it was a matter of living or dying. Over a period of weeks, I came to know that this was her journey. I felt acceptance of the possibility that she might die, while still allowing myself hopes of her wellbeing. I came to love and accept her on her terms.

The spotting continued, with occasional clear days, for more than six weeks. After the initial shock wore off, and it became clear that nothing was happening fast, I began to relax more. Finally, when I was nearly twelve weeks pregnant, I began experiencing nausea and vomiting. I cannot express how I welcomed these signs of pregnancy! Finally, when I was nearly fourteen weeks pregnant the spotting stopped altogether, but by that stage I was confident of my baby’s wellbeing by virtue of vomiting and pronounced breast changes. My pregnancy continued normally, and, aside from daily vomiting until twenty weeks gestation, was a joy. I gave birth at home to a gorgeous healthy baby girl.

After nearly three years of breastfeeding my daughter, I began to experience occasional and erratic spotting over a period of about six weeks. I assumed (rightly) that my body was finally preparing to ovulate and menstruate again. After such a long time without a fertility cycle, the possibility of conception felt abstract. I was interested in using the fertility awareness method to prevent pregnancy, but was preoccupied, and did not bother to resume charting my fertility signs. Nothing followed that initial period of spotting. At first I thought nothing of it, assuming that my hormonal balance had simply swung back towards lactational amenorrhea. Ever so slowly, however, the idea began to grow that I might be pregnant. While my partner and I were both keen to have another child at some stage, I had just qualified as a midwife, and had a strong desire to work for several years before taking a break for a new baby. I was horrified to even think that I might be pregnant, so fixed were my plans. Despite my internal anguish in supposing the possibility of pregnancy, I had no desire to confirm or refute that possibility using a pregnancy test (though I was carrying some in my own kit!). I recognized that abortion was not an option for me, and adoption was not an option for my partner. There was therefore nothing that I would be ‘doing’as a result of ‘knowing’ of the pregnancy.

Mirroring the experience of my first pregnancy, I found comfort in uncertainty. Once again, hope and despair lay together within me, this time attached to opposite outcomes. I prayed not to be pregnant, and dreaded to find myself so, which would require a rearrangement of my so-precious plans. Over a period of several weeks I began to see the situation in a new way. I was forced to acknowledge the hypocrisy inherent in my resistance to the possibility of pregnancy; I was so determined to spend my time helping other people welcome their babies with gentleness and love, that I was unable to find it within myself to do so for my own child! As I firmly believe that babies in the womb are affected by their mothers’ emotional state, I could not deny that, if I were indeed pregnant, I would wish to protect my child from such a hostile reception. I began to find myself wanting to offer the best I could manage for what was still, up to this point, a hypothetical child. I had finally accepted the idea of this child, and within a few days I began to experience nausea and fatigue. The hypothetical became real – I knew I was pregnant. A healthy pregnancy flew by, and I gave birth at home to a beautiful baby boy.

I do not pretend that my adjustment and acceptance of the pregnancy was entirely smooth, and new pockets of resistance surfaced through the pregnancy, and even after the birth. But my fundamental agreement to do my best for this child supported me, and I acknowledge those challenges as part of my relationship with my son. Some might argue that, had I taken a pregnancy test when I first conceived the possibility of pregnancy, my emotional adjustment might have been faster. With sure ‘knowledge’of pregnancy, perhaps I would have seen my child’s perspective sooner and willingly relinquished my resistance. Perhaps such a scenario would support some women’s inner processes, but for me emotional change occurs in its own time. Had I been sure of my pregnancy before my attitudes had time to evolve, I suspect my anger and frustration would have been magnified and directed at my child. By avoiding a technological confirmation of pregnancy, I believe I was subconsciously protecting my son from an experience of total and unalloyed rejection.

Several commonalities run between these two very different pregnancy stories. In each, the state of not ‘knowing’ allowed the time and space for emotions to change and new awareness to grow. In both cases physical signs confirmed my pregnancies once the intense period of emotional upheaval was resolved. I stand in awe of the process that allowed me time to feel, before I could not help but ‘know’. I value my experiences in the early stages of both pregnancies for offering me greater self-knowledge, and helping to prepare me for the task of mothering. I fully acknowledge that every woman’s path is different, but I wonder how much of our inner journey we deny by turning immediately to technology to bring knowledge of our pregnancies.

Since redoing the website previous links for my very early critiques of the Term Breech Trial have changed. As I have been repeatedly asked for these I have linked them anew: Term Breech Trial commentary and Breech birth beyond the Term Breech Trial.

Artist: Stewart Fulljames, Rewa Gallery, New Zealand

In this review of newborn and maternal physiology following birth, Dr Sarah J Buckley focuses on the importance of supporting the newborn’s transition by delayed, or no, umbilical cord clamping.

The third stage of labour, delayed cord clamping or, simply, non-interventionist birth?

The third stage of labour is a powerful and mysterious time; more important than we acknowledge and more complex than we know. These thirty minutes or so, which begin as the mother births her baby and finish as she births her baby’s placenta, are usually uneventful compared to the drama of labour and birth, leading many (including many care providers) to think that the birth is already completed. However, enormous changes are happening in the brain and body of mother and baby, all of which are crucial for their survival in the short, medium and long-term. The substantial contribution of the third stage to species survival predicts that evolutionary investment will be high, with substantial sophistication incorporating multiple systems and adjustments.

For the mother, the major adjustment is the shift from pregnant to non-pregnant and especially the sudden separation of her baby’s placenta, which has been intimately associated with her cardiovascular system for the duration of her pregnancy. As the baby’s placenta peels off her shrinking uterine wall, rather like a postage stamp peeling off a deflating balloon, she must seal the blood vessels on her side so that her uterine blood supply, flowing at one-half to one litres per minute, will not haemorrhage from the torn vessels.

This physiological miracle is accomplished by the mother’s uterine muscle fibres, which begin to contract and retract immediately after birth forming “living ligatures” that tighten like a purse-string, kinking and sealing off each maternal arteriole. The uterine contractions that provoke this life-saving haemostatis are triggered by surges of oxytocin, released in a crescendo from the new mother’s pituitary as she gives birth. Ongoing maternal pulses of oxytocin are released as she gazes at and touches her baby, and as her newborn massages, licks, and finally suckles her breast Matthiesen et al (2001). Maternal oxytocin levels peak around the time of placental expulsion Nissen et al (1995) and, in all mammals, oxytocin plays a major role in switching on instinctive mothering behaviour at this time Nelson & Panksepp (1998).

Other hormonal systems are also active in the new mother’s brain and body to adapt her to her new maternal role. These include beta-endorphin, the body’s natural opiate and a hormone of attachment, which peaks at birth: adrenaline and noradrenaline, which are elevated in the minutes after birth and ensure that both mother and baby are wide-eyed and alert at first contact (noradrenaline is also a hormone of attachment) Nelson & Panksepp (1998); and prolactin, which reduces stress and augments maternal behaviour Grattan (2001) likely also beginning its role as the major hormone of breastmilk synthesis during and soon after labour and birth.

Postpartum elevations of these hormones, which are even higher and more sustained within the brain than levels measured in the bloodstream Gimpl & Fahrenholz (2001),ensure the devoted maternal care that will optimize offspring survival through to reproductive maturity, and that will be replicated by female offspring with their own young Pedersen & Boccia (2002).Newborn and maternal hormone elevations in the hour following birth also ensure an optimal start to breastfeeding, as initiated by the baby and supported physiologically, hormonally, and behaviourally by the mother Buckley (2009).

For the baby, the major changes during third stage involve the respiratory and cardiovascular systems. These two immediate adjustments, both crucial for survival, are interrelated and both require the extra volume of blood that Mother Nature provides for an optimal newborn transition.

An ongoing supply of oxygen is a physiological necessity, and so, beginning at birth, blood is rerouted away from the placenta (which is reducing its oxygenating capacity) and towards the newly-functioning lungs. Over this time, the pulmonary blood flow increases from 8 percent of foetal cardiac output to 40 percent in the newborn, with this extra blood filling the alveolar capillaries, where oxygenation takes place.

Newborn circulatory rerouting involves the closure of the shunts from umbilical cord to liver and heart, (ductus venosus); from right to left atrium (foramen ovale) and from pulmonary trunk to descending aorta (ductus arteriosus), most of which are aimed at supporting the new pulmonary circuits.

Other major roles of the placenta, chief waiter in the “hotel de womb”, must also be performed by the newborn kidney, liver, gut, and skin. These newly-functioning organs, whose vascular beds were relatively unfilled in-utero, also require extra blood for optimal perfusion and function.

Mother Nature’s superb design for this time involves a gradual redistribution of blood in the minutes after birth, adding up to a substantially-increased blood volume in the newborn, compared to the foetal, body. This haemotological top-up, known as the placental (or placento-foetal) transfusion, comes from blood that is temporarily held in the placenta and is transferred to the newborn in several stages.

According to Dunn (1984), during the baby’s final passage through the mother’s lower vagina, pressure on the cord obstructs the low-pressure umbilical vein, which prevents blood returning from placenta to baby and results in an increased blood volume within the placenta. (The higher-pressure artery is not affected, so that blood can flow from baby to placenta but not back again).

This placental back-log may help to delay placental detachment by making the placenta more rigid. Delayed detachment gives the newborn an ongoing source of oxygenated placental blood that is an important back-up, especially if the baby is slow to breathe. Observations that the first five or so newborn breaths are not effective in gas exchange Ullrich & Ackerman (1972) and that placental respiration continues at normal efficiency for at least 37 seconds after birth Marquis & Ackerman (1973), underline the importance of this back-up system for all newborns.

As the baby emerges, pressure on the umbilical vein is released and the bolus – around 66 mL – of warm, oxygenated, pH-balanced blood that was back-logged in the placenta enters the baby’s circulation Dunn (1984). This occurs within seconds of birth, as evidenced by two studies in which weight gain (reflecting incoming blood) has been continuously recorded from birth Diaz-Rossello (2006).

This placental transfusion, also called the placento-foetal redistribution, is augmented by the new mother’s third stage contractions, which compress the in-utero placenta and so push blood towards the baby. Between contractions, blood can return from baby to placenta through the umbilical vein, which closes later than the artery, and which can transport blood in either direction. This transfusion takes place over several minutes, with the majority of blood transferred within three minutes of birth.

The final amount of blood that is transferred from placenta to newborn can vary from 54 to 160 mL Usher et al (1963), implying that different babies have different circulatory needs and also suggesting that newborns can self- regulate their final blood volume. This may happen through adjustment of umbilical vein flow or other means: Gunther (1957), who continuously recorded newborn weight after birth, showed a reduction in weight (therefore a transfer of blood back to the placenta) during a crying episode, likely due to increased systemic pressure.

The average newborn blood gain following the placental transfusion is around 100ml. Diaz-Rossello (2006), who also recorded newborn weight gain showed a final average weight gain of approximately 100g; equivalent to 100ml of blood. This is around one-third of the total blood volume of an average term newborn (300-350 ml), and so represents a major circulatory contribution.

This blood is also rich in protein and nutrients (containing, for example, the equivalent iron in 100 litres of breastmilk Zlotkin (2002)); in red cells (delayed clamping increases red cell numbers by up to 60% Yao et al (1969)) and in haematopoietic stem cells, which will migrate to the bone marrow and differentiate into various blood and immune cells. The deliberate withholding of newborn blood for so-called “cord blood banking”, which involves taking all or most of this 100ml, has no discernable benefit to the baby Diaz-Rossello (2006) and we have not investigated the harm that may result from deprivation of newborn stem cells Buckley (2009).

The extra blood volume, as well as its components, is also important for an optimal transition. Mercer’s model of neonatal transitional physiology Mercer & Skovgaard (2002) demonstrates the importance of adequately filling the pulmonary capillary networks that surround each alveoli and which, when filled with blood, make the alveoli erect, even before lung inflation. According to studies by Jaykka (1957), the pressure needed to inflate the lungs is substantially lower when the pulmonary vascular beds are pre-filled and the alveoli are erect.

The placental transfusion also aids the clearance of the fluid that fills the foetal lungs, which is optimized by the high levels of plasma proteins associated with a full placental transfusion. Good levels of plasma proteins ensure that the blood colloid osmotic pressure (COP) is high enough to pull the more dilute lung fluid across the alveolar membrane and into the blood stream by osmosis. Both volume and COP effects will optimize newborn lung function, and may be compromised by early clamping.

The baby whose cord is clamped immediately after birth, especially within the first ten to twenty seconds, will lose not only the nutrients, stem cells, and red cells, but also the extra blood volume and will be hypovolemic, to a greater or lesser extent Dunn (1984). Diaz-Rozello (2006) comments, “For the neonate, it is as if 25% of its volemia is bled into the placenta (p. 559).”

Recent randomized controlled trials of early versus delayed cord clamping have highlighted the extra risks of iron deficiency and anaemia in infancy associated with early clamping, compared with a delay of even 30 seconds. A 2007 meta-analysis, published in JAMA, suggests that early cord clamping increases the risk of anaemia by five times at one to two days; and doubles the risk at age two to three months, compared to late-clamped babies. In this analysis, early clamped infants also had lower iron stores at six months Hutton & Hassan (2007).

Concerns about jaundice are often raised in relation to delayed cord clamping. After birth, any red cells that are excess to newborn requirements will be broken down, with red cell haeomoglobin being converted to water-soluable biliverdin and eventually to fat-soluble bilirubin. Higher numbers of red cells associated with delayed clamping are therefore likely to cause some degree of jaundice, which occurs among all newborn mammals and is probably an important and deliberate postnatal adaptation. Bilirubin is a potent antioxidant that can protect newborns from the sudden “hyperoxia” that occurs with the transition from low oxygen levels in the womb to high levels on exposure to room air Sedlak & Snyder (2004a).

This “beneficent” role of bilirubin Sedlak &, Snyder (2004b) was confirmed in a 2008 study Shekeeb Shahab et al (2008), which showed that mild to moderately jaundiced newborns have better antioxidant status than less jaundiced babies, which deteriorates when phototherapy is used to reduce bilirubin levels.

Note that studies do not show an excess of severe jaundice (such as would cause kernicterus, or brain damage) in babies who have had late clamping. Two recent reviews, including more than 1000 late-clamped babies, both concluded that phototherapy or exchange transfusion for jaundice were no more common among late-clamped compared to early-clamped newborns Hutton & Hassan (2007); van Rheenen et al (2006).

Jaundice is also mentioned as an outcome in the recent Cochrane review of the timing of umbilical cord clamping McDonald & Middleton (2008). The reviewers concluded that jaundice requiring phototherapy may be increased with delayed clamping: this conclusion is counter to the two reviews mentioned above, and is critiqued in detail elsewhere Buckley (2009).

Similarly, concerns that “overtransfusion” from delayed clamping will make the blood of healthy newborn babies too thick (polycythemia) and cause “hyperviscosity syndrome”, where extremely viscous blood cannot flow through the small vessels, are not based on good studies Mercer & Skovgaard (2002). As the authors Hutton & Hassan (2007) of the JAMA review conclude:

“Delaying clamping of the umbilical cord in full-term neonates for a minimum of 2 minutes following birth is beneficial to the newborn, extending into infancy. Although there was an increase in polycythemia among infants in whom cord clamping was delayed, this condition appeared to be benign (p. 1241).”

Although the above discussion is generally focused on healthy term newborns, it is important to note that premature babies are at even greater risk from early clamping, because the preterm placenta is relatively larger relative to the body and holds more blood to be transferred to the baby. Cochrane guidelines are unequivocal about the importance of delayed clamping in premature newborns Rabe et al (2004).

Compromised newborns may especially need the blood and oxygen that the placental transfusion provides. Ironically this group is especially likely to have their cord clamped early and be taken away for resuscitation, often because resuscitation facilities are further than a cord-length away. UK obstetrician Andrew Weeks advocates allowing compromised newborns at least one minute for placental transfusion, and comments: “In these days of advanced technology, it is surely not beyond us to find a way of keeping the cord intact during the first minute of neonatal resuscitation Weeks (2007, p. 313).”

Similarly, babies born by Caesarean are very likely to miss their placental transfusion: Weeks recommends that surgical staff “wait a minute” before clamping the Caesarean baby’s cord, with the baby kept warm on the mother’s legs Weeks (2007).

Thankfully, international studies and guidelines are beginning to acknowledge harms from early clamping and promote a normal neonatal transition. Weeks concludes: “There is now considerable evidence that early cord clamping does not benefit mothers or babies and may even be harmful.” and recommends a delay of three minutes, with the baby on the mother’s abdomen Weeks (2007). The UK RCOG has also acknowledged possible harms of early clamping on infant iron status Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2008), and comment “It is increasingly difficult to justify routine early cord clamping, especially for preterm births Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (2008, p. 3).”

A recent joint statement by the International Confederation of Midwives and the International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians, as part of the Safe Motherhood project International Confederation of Midwives & International Federation of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians (2004) also advocates that the baby’s cord should not be cut until pulsation has ceased. (The role of oxytocics, which are still advocated under this new form of “active management”, is discussed elsewhere Buckley (2009)).

A physiological transition for mother and baby would, to my mind, exclude the cord clamp altogether, with the cord cut only after the mother has birthed her baby’s placenta, at which time very little blood is spilled with cord cutting. Non-severance of the cord (lotus birth Buckley (2005, pp. 40-43); Rachana (2000)) is another way to ensure a full physiological transition for mother and baby.

In conclusion, we can trust Mother Nature’s superb design for mothers and babies in third stage, as well as in birth. For healthy mothers and babies, for Caesarean newborns, for premature babies and for babies who require resuscitation, an optimal transition can be supported by leaving well alone in the third stage of labour.

Drying and shrinking umbilical cord and placenta with Jacob’s lotus birth

This post was originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2009; 1: 29-34. Sarah J Buckley is a New Zealand-trained General Practitioner, mother of four homeborn children and author of the internationally-acclaimed book Gentle Birth, Gentle Mothering. She lives in Brisbane, Australia.

This post written by Heather Wallace was originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2010; 5: 33-36.

A midwifery stitch

Last year I returned to clinical practice after an extended maternity leave of almost five years. I was concerned that I would be completely out of touch and that my time out from the workforce would result in big black gaping holes in my practice and knowledge base. However I was pleasantly surprised to discover that on return to work as a midwife, rather than be jeopardised, aspects of my practice have actually been enhanced by my labouring/birthing/mothering journey—growth and enrichment as a woman has ultimately resulted in growth and enrichment as a midwife.

Three personal journeys of labour and birth for ‘Heather the Woman’, three ‘key’ lessons for ‘Heather the Midwife’! I share these with you now—with a little bit of ritual, myth and magic around the edges!

It all began with the unification of Europe. My husband Rod and I were driving and camping our way around Western Europe in the early stages of the creation of the European Union. We reached Portugal and discovered that on one stretch of road one was likely to be met by carts being pulled by donkeys, while just around the corner a mammoth vertebrae of freeway awaited completion—Portugal, it seemed, was being hauled into the EU via the Auto strata. This complete overhaul of the Portugese roadways resulted in our trusty atlas being entirely inaccurate, leading to the barney of all barneys between navigator (me) and driver (Rod), and then a long stony sulky silence. To pass the time while not speaking to one another, I read the Spanish Lonely Planet in great detail, and discovered that our drive out of northern Portugal would take us over the border, into Spain and very close to a tiny village with special midwifery significance. Speaking again, we made our way to A Ramallosa, where a medieval bridge spans a deep green river. Legend has it that for hundreds of years women at about 12-14 weeks gestation would visit the bridge, bring offerings to the stone deity in the centre, and ask for a safe and easy passage through labour and birth. It is a beautiful bridge, with its image echoed in a blue and white tiled mural in the centre of the village. I crossed the bridge, made an offering in the centre, asked for a blessing, had my photo taken by Rod and we then continued on our way. But myth, magic and ritual are powerful and often enduring phenomena!

Lesson 1—Trust the process

A Ramallosa bridge

http://www.baiona.org

Years later, Rod and I were delighted to discover that I was pregnant. We promptly adopted two standard poodle puppies to “practise” being grown up and responsible. I ‘booked in’ to the Birth Centre of the large public hospital where I was working at the time, plus had ‘shared care’ with an Obstetrician—just in case! I had a Glucose Tolerance Test and Group B Strep swab—just in case, and was quite compliant and unquestioning when the Obstetrician said an emphatic no to birth in water. Having what felt like hundreds of people say to us during my pregnancy “Ohhhh—a midwife married to a doctor—you’re going to have a terrible time in labour” helped to prompt me to do everything I could to optimally prepare for my labour, with lots of yoga and aqua-aerobics. And not to forget—I had crossed that medieval bridge!

My waters broke in the late afternoon of a July winter’s day. There were no contractions. “Right” said Rod “Time to walk”, so gathering poodles we set off along the beach, assuming we were at the beginning of a 24 hour process. Let’s just say that a five kilometre beach hike did a much better job than a truck load of syntocinon, and by the time we got home things were ‘established’. Not wanting to get too excited, conscious of the ‘text book labour’ times described during our education plus the sentiments from all the ‘doubting Toms’, both Rod and I tried to play down the significance of what was happening. Also, I didn’t want to turn up at the Birth Centre and have my friends and colleagues tell me I was only 1cm dilated with a posterior cervix! I tried describing to Rod the ‘anal cleft’ line in an attempt to determine what my cervix was up to. Rod found some kind of line (in hindsight, a knicker-crease), pronounced “two centimetres” and I retreated to the bath. Half an hour later having bowel pressure and having to drop to the ground in ‘child’s pose’ to get through each contraction, still not believing that this was actually labour and worried about being sent home, Rod bundled me into the car and we were off to the Birth Centre. An hour later, in the bath, cared for by a supportive and wise midwife, (the Obstetrician was thankfully detained at a hospital around the corner!), I breathed my baby out of my body and became a mother. As I scooped up my slippery, warm, wet baby, any doubts about the abilities of my body disappeared, and I knew that my body was made for birthing.

Lesson 2—Respect the uterus.

A couple of years later it was time for labour number two in a new city at a new Birth Centre. Again, waters broke with no contractions, so off we all went along the waterfront for a ‘kick-start labour’ walk. With my body slower to come to the party this time around, I called the hospital to let them know what was going on (that is, SROM with no contractions) and what I was planning to do about it (that is, walk!) Unfortunately the midwife (who I did not know) was not happy about a “multi” lurking in the community with ruptured membranes—heavens, my baby could drop out on the footpath! She was all for me being admitted for monitoring and Syntocinon. Thankfully I had become less compliant this time around, plus more ‘trusting of the process’—oh—and don’t forget that bridge! During her lecture on infection, safety, what’s best for baby etc, she let slip that my favourite midwife was starting work at 9pm—suddenly I had a time frame! I bid the unknown midwife farewell, settled back and waited, and yep—at 8.55pm, my contractions started! It wasn’t long before Rod was not happy with me lurking at home, so it was off to the Birth Centre, into the bath and then oh my goodness—the power, the intensity, the ferocity of my labour! Whereas with my first labour I had felt my mind and body work in unison and harmoniously, this time around there seemed to be a real ‘power imbalance’ between the two, with my uterus totally calling the shots. Three hours later I was scooping my baby up out of the water onto my chest for “that” million dollar feeling, Rod was sending the ‘birth announcement’ text message—“No drugs, no doctors, no stitches, no worries”, and I was feeling a little like the Pony Express had travelled down through my pelvis and then turned around and trampled right over the top of me!

Lesson 3—There’s no place like home

With pregnancy number three, I gave up on compliance all together and chose to birth my baby at home. I also resumed my yoga practice, had a friend coach me in some visualisation and meditation, and so ‘returned to the breath’. I felt ready to have my baby at 38 weeks, but had to stall for a couple of days due to Rod having ‘Man Flu’. Finally, it was time. I am nothing if not predictable—waters broke—no contractions—poodles—ocean—walk! Filling the birth pool was an exercise requiring metres and metres of purple hose, two hot water systems and a lot of yelling! Rod was running around hooking the hose up to various taps while I was supposed to be filling the pool. However, because I was bent over the edge of the pool engaging with pelvic rocking and breathing through my contractions, I wasn’t entirely focused on where the end of the hose I was holding was or how much I was sloshing the water over the side. Minor flooding, running out of hot water before the pool was filled and then Rod smashing a window while trying to manoeuvre the hose around some outdoor furniture, all contributed to the “this wouldn’t happen in a hospital” atmosphere! Finally I could get in the pool, breath and let my body do its thing. Things were hotting up—I was working hard, breathing hard and I felt as though I was using every ounce of ‘mental stamina’ to stay focused and effective. As I was reaching what felt like a crescendo, I opened an eye to see Rod bending down toward me and I felt such relief, as I assumed he was reaching down to talk me through my contractions and help me chant the special mantra we had devised together for this very point of my labour—what a lucky woman I was to have a partner so ‘in tune’ with what I was up to and just knowing when I needed that extra bit of encouragement and support! As his lips grazed my ear and I waited for those special words, he said “I’m just going to chop the wood”! Needless to say that was not the mantra! He went and chopped the wood, I got on and birthed my baby! Although it has been nicknamed the ‘Faulty Towers of Home Births’, in all seriousness, to have had the opportunity to birth at home and all that that entails, has been a most empowering, rewarding and enlightening experience.

Personal labour and birth journeys now complete, mothering and midwife journeys—works in progress!

Post script

Later this year I will be returning to the ‘Bridge of Good Labour’ in A Ramallosa. This time, I will take my three water babies with me. I aim to share with them the significance, myth, magic and ritual associated with the bridge, and as a result how it fits in to their personal stories. In the centre of the bridge I will give thanks for my birthing experiences and blessings, and then I’ll cross that special bridge—a little bit older, a little bit wiser, with a whole lot more water under than a decade ago! A woman and a midwife, enriched by becoming a mother.

A midwife’s belief in a diverse society, and her knowledge of the joys a child with Down syndrome can bring, is reflected upon in this post by Kim Porthouse. She addresses the ‘burden’ that can arise in ensuring informed choice for women in relation to Down syndrome screening. Originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2009; 2: 14-19.

With every booking visit I battle with an internal dilemma; the issue of discussing pre-natal screening fills me with trepidation. I am a midwife in my second year of Lead Maternity Carer (LMC) practice. I am also the mother of two sons, one of whom (Brendon, pictured below) has Down syndrome. In this article I discuss how being Brendon’s mother impacts on my practice as a midwife.

In 1994 I was pregnant with my first son at the age of 32. I had initially decided on ‘shared care’ between my doctor and a midwife but I later changed to midwife-only care.

In 1994 I was pregnant with my first son at the age of 32. I had initially decided on ‘shared care’ between my doctor and a midwife but I later changed to midwife-only care.

Routine pre-natal screening – Nuchal Translucency (NT) scan and Maternal Serum Screening (MSS2) - were not on the radar then. However, my doctor, who had also had her children in her 30s, was very keen that I should have an amniocentesis to check for chromosomal abnormalities, particularly Down syndrome. She informed me that, as I was older, I was at higher risk. When I asked about these risks, she told me that at my age I had about a 1:450 chance of having a baby with Down syndrome and that amniocentesis had a 1:100 chance of miscarriage. (I have since learned that the chance of having a baby with Downs at 32 is actually about 1:650.) She also told me of her amniocentesis with each of her children; it had been a simple procedure which gave her such peace of mind. If mine came back positive, I could be offered a termination. She told me that it was recommended for all women aged 37 years and over but she thought it should be offered more widely.

I had been fortunate that about 10 years previously I had worked for the Intellectually Handicapped Society (IHC) for a few months, therefore Down syndrome was something I had come across and about which I had an understanding. I knew that if my baby had Down syndrome I could love it. I guess that was all I needed to know. I also knew that termination was not an option that I could go through with and I would not put my pregnancy at such a high risk of miscarriage. I therefore declined amniocentesis. My first son Chris was born and he was ‘normal’.

Three years later at the age of 35, I was pregnant with my second son; it had taken me 15 months to fall pregnant. A good friend of the same age was pregnant with her first child. She told me she was having an amniocentesis and would terminate if there was anything wrong. I found it amazing that she could be so black and white. I found her fear of disability astounding. This made me consider the issue again for myself. My risk of having a baby with Down syndrome was now 1:350 and the recommended age for amniocentesis had recently been lowered to 35. However, I quickly decided that this test was still not right for me and I could not risk miscarriage of this much wanted baby. My second son Brendon has Down syndrome.

Nothing could have prepared me for the griefthat consumed me with the news of Brendon’s Down syndrome. It was like a physical pain in my chest; my hopes and dreams were shattered, and I didn’t think I would ever stop crying. I felt I was being punished for wanting another child when my husband would happily have stopped at one (he had two other older children). I felt isolated, alone and different. I felt like a failure.

When told Brendon had a heart defect, I didn’t feel much about this at first; I couldn’t get past the words ‘Down syndrome’ but over the next couple of days it all sunk in and my concern grew. My baby had a life threatening condition. Somehow Down syndrome didn’t matter so much anymore – what was most important to me was that my baby lived! I was still hurting, still upset and feeling very cheated. I was scared of all the unknowns but I became increasingly aware that I wanted my child no matter how he was packaged. Deep inside I knew I could live with Down syndrome. Deep inside I believed this child has a right to life – after all, that was all part of the decision not to have amniocentesis. I began to know my grief was about shock, and about the loss of what was expected rather than about ‘what is’.

Brendon was so sick that at first I was only allowed to hold his hand. He was also very agitated. After three days they finally let me hold him. As I held him and we looked at each other, his jerky movements began to ease and he became totally calm. I could feel my own tension draining from me as I felt him relax. As Brendon fell asleep in my arms, I could finally let all my maternal emotions flow out to him. This was a turning point for me; I knew he needed me, and I was besotted. Although there was still sadness, the healing process had begun. (It is vital women get to hold their child as soon as possible after birth. Both mum and baby need time to be as one. The midwife needs to be the protector of this and, even when the baby is very sick, she needs to find a way to bring mum and baby properly together.)

For 11 years now Brendon has been the source of such immense pride and joy. He has enriched my life in ways I never would have imagined, and he has touched the lives of many in such a positive way. Mostly Brendon is easy to live and get along with. Yes, my life has been changed by Down syndrome. Yes, life has seemed hard at times, and there have been some frustrations and difficulties. The hardest thing, however, is individual and societal attitudes to disability and the non-acceptance of such diversity. I am blessed to have my son, and I have no regrets. At times normal children are challenging to parent and provide their fair share of frustrations; these are just different than those of a child with Down syndrome. Who has the right to say which child is a worthy challenge and which one is not?

For 11 years now Brendon has been the source of such immense pride and joy. He has enriched my life in ways I never would have imagined, and he has touched the lives of many in such a positive way. Mostly Brendon is easy to live and get along with. Yes, my life has been changed by Down syndrome. Yes, life has seemed hard at times, and there have been some frustrations and difficulties. The hardest thing, however, is individual and societal attitudes to disability and the non-acceptance of such diversity. I am blessed to have my son, and I have no regrets. At times normal children are challenging to parent and provide their fair share of frustrations; these are just different than those of a child with Down syndrome. Who has the right to say which child is a worthy challenge and which one is not?

Since having Brendon I have met so many amazing families. We all share the story of grief and deep sadness at the births of our differently-abled children. However, we all also share the stories of great happiness and enrichment that our children have bought us.

I am so frightened by the way people view disability and think that it can only bring hardships. I worry about how people make decisions about screening based on their fear of the unknown, and how they believe they wouldn’t cope. My experience is that people cope and rise to the challenge and generally find their life enhanced by their child.

I am also frustrated by the focus of screening out children with Down syndrome. To me, it implies that having a child with Down syndrome is a really bad thing, which it is not; it is simply different. The implication is that if a child has Down syndrome (or Spina bifida, our other widely screened for condition) that these children’s lives are not worthwhile and that they have nothing to offer to society or their families. I find this implication offensive. Many people with disability grow up to hold jobs and be active, contributing members of society. Perhaps if women choosing amniocentesis for a positive screen were offered the opportunity to receive information and/or contact from the New Zealand Down Syndrome Association (NZDSA), they could be well informed about living with Down syndrome and consider all their options whilst waiting for a result.

Screening does not diagnose normality; it only measures specific markers, which are used to calculate and provide a risk analysis. There is a belief that if women screen for Down syndrome and have a negative test then their child will be normal.

So many people do not seem to realize that there is a diverse range of disability and, conversely, ability. Most conditions cannot be screened for and normal karyotyping (determining the appearance of individual chromosomes) provides no guarantee. For example, I know a family who had normal karyotyping on amniocentesis and yet, when the child was born, she had a structural abnormality of the brain that meant she was severely disabled.

I know I am not the only midwife with a child with Down syndrome, and I cannot speak about how others feel on this issue, but these experiences and thoughts contribute to my internal turmoil. In one corner is my personal story, my own feelings about termination, my passion for the rights of children with disability, my belief in a diverse society and my knowledge of the joys and love a child with Down syndrome can bring. In another corner is my sadness at society’s non-acceptance of this diversity, and the hardships parents can face because of that non-acceptance.

In yet another corner is the feeling that I, more than anyone, absolutely have to offer every woman pre-natal screening, not because I think it is a good thing but because I have a child affected by the condition for which screening is available. What if I didn’t discuss it and then someone had a child with Down syndrome? It wouldn’t be long before they found out I have a child with Down syndrome – after all, my family is featured in a ‘We Welcome Your Baby’ pack and DVD produced by NZDSA. Would I then be accused of not fully informing women of their choices, of deliberately not offering screening, or, of influencing their decisions?

I have to be so careful of the language I use, and not present this issue with bias. I’m sure every midwife has a bias on whether she thinks screening is better or worse for society. I wonder, though, how many feel the same pressure to phrase the issue in a non-biased manner? How many midwives even think about how their language and presentation might influence a woman’s decision?

I feel I have to keep the fact that my child has Down syndrome a secret, in case people would feel uncomfortable about choosing to screen and feel unduly influenced by this. I hate to deny this facet of my child’s existence; I am proud of my son and I do not apologize for his Down syndrome and yet, as a midwife, I feel compelled to hide it from the families with whom I work.

Whilst I absolutely believe that women need to make their own decisions whether to screen or not, and not be led by the health professional, why do I feel I have to present such a neutral front? When women ask me what I think, why do I feel I can’t share my view in case it is interpreted as trying to influence them? It may be that my story may affirm their own feelings rather than challenge them, yet I can’t take that risk. I allow women to make decisions based on preconceived ideas of Down syndrome. I ask myself – why is it I feel I cannot talk about the positive aspects of parenting a child with Down syndrome? After all, couldn’t this information be given as part of fully informing women about Down syndrome along with medical descriptions of disability?

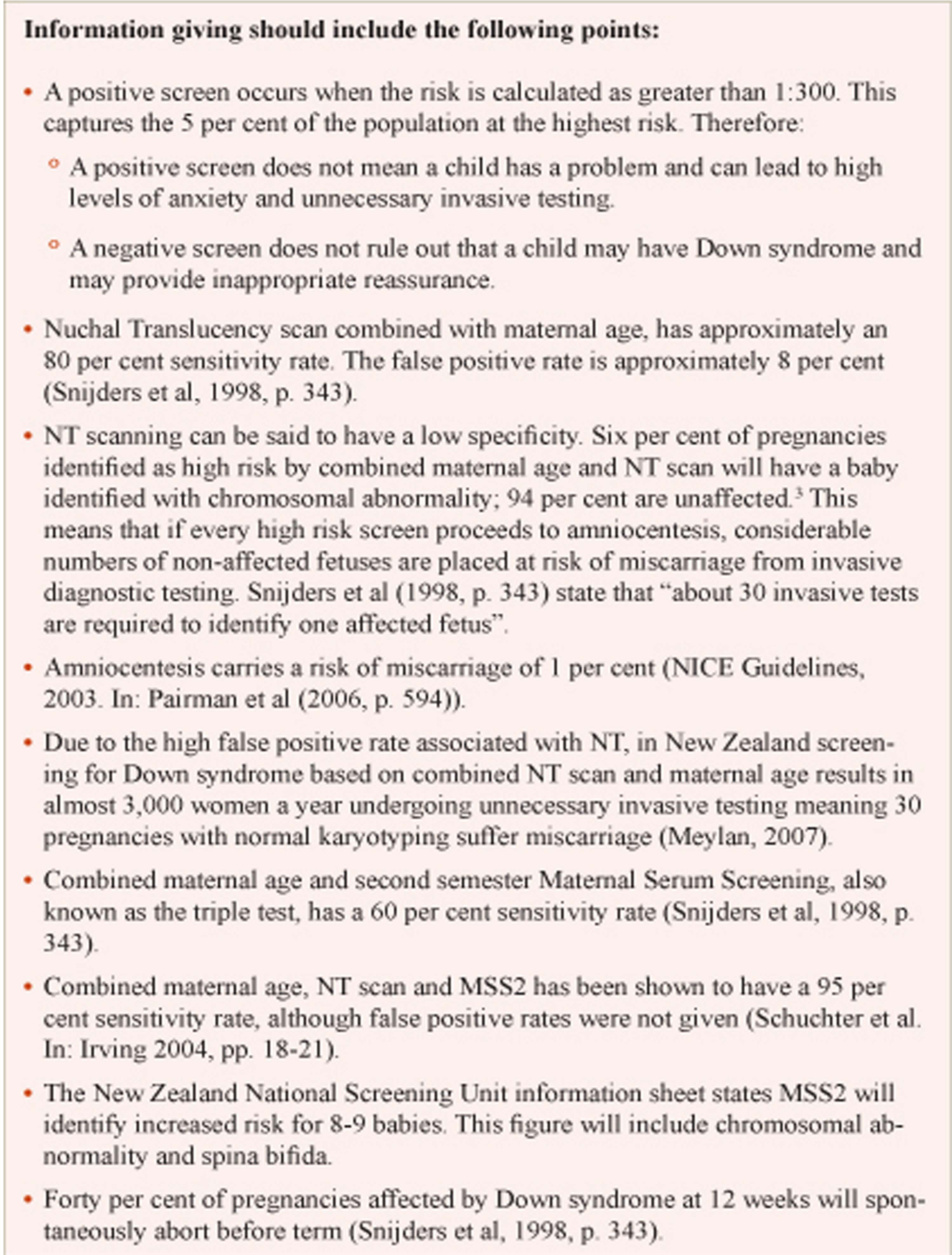

Snijders (1998, pp. 343); NICE Guidelines, 2003, in Pairman et al (2006, p. 594); Meylan (2007) [hyperlink]; Schuchter et al. In: Irving (2004, pp. 18-21)

Sometimes I am offended when women say they want to screen because they wouldn’t want one of ‘those’ children. I want to ask them if they know and have firsthand experience with any of ‘those’ children, and what is it about ‘those’ children that is such a problem. I want to tell them of Brendon and that my life is not ruined by him; my life is good. However, I just nod and say okay and fill out the forms. I feel such relief when someone chooses not to screen.

Application to Midwifery

The Ministry of Health (MOH) has provided funding for NT scans within the Section 88 Notice MOH (2007). It has funded MSS2 screening with the recommendation that NT should not be used in isolation but in conjunction with MSS2 – one combined result being provided to women.

There is, however, debate as to the robustness of these screening tools and whether they meet the criteria for introduction. Tests should be simple, sensitive, cost-effective and reliable, and there should be effective, acceptable and safe treatment Irving (2004, pp. 18-21).

The MOH has placed an expectation on LMC’s to offer these screening tools to women. Currently in New Zealand midwives receive no training on how to counsel women about pre-natal screening. Nor do midwives receive any training or advice on counselling the women and their families that receive positive screen results. Should we as midwives even be offering women screening if we haven’t had such training?

Midwives are autonomous practitioners. We need to ask ourselves why we should include this screening in our practice – is it just because it’s available, or, are we obliged to offer it because New Zealand women have the right to be fully informed? If as a profession we believe we must offer screening then there is a need to take responsibility for ensuring midwives are provided with adequate education and training. Midwives must be provided with the accurate, objective information with which women can be fully informed. Women need to be given information that provides a balance of perspectives so that they have the power to make informed, not just emotive, decisions. As a profession we also have a responsibility to ensure that there is nationwide consistency regarding what screening is available and what is offered to women. We should be ensuring that when screening is offered that women are offered the most accurate options available.

When considering this issue we must ask – what is the MOH motivation for wanting screening introduced, and, is it about what is ‘good’ for society? The main motivation is most likely about money – screening to prevent Down syndrome is probably cost effective to the health and education sectors. If the MOH expects us to offer screening then perhaps LMC’s should expect the MOH to fund adequate training programmes. Perhaps the New Zealand College of Midwives could seek funding from the MOH for this purpose and assist the implementation of a national education programme on screening, which could also include other screening issues such as HIV.

In summary, I see the challenge for midwifery is to be informed, objective, and balanced in the presentation of this issue. Midwives need to be respectful of the sensitivity of this issue and of individual views; pre-natal screening is a highly personal, emotive and culturally sensitive arena. In all reality pre-natal screening for Down syndrome is here to stay. I hope my story has highlighted there are two sides to this issue and that it will encourage midwives to examine their own feelings, as well as their discourse when talking to women.

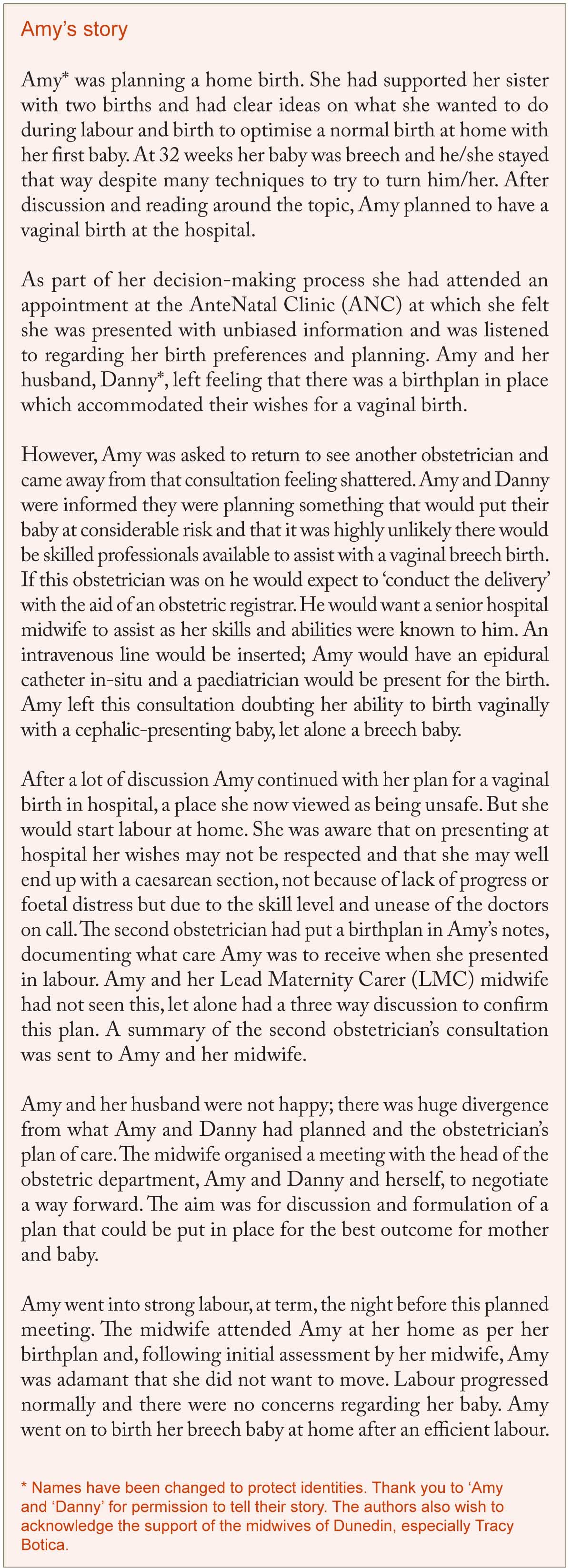

A multi-disciplinary hospital meeting to air issues raised by women’s feelings of dissatisfaction with obstetric consultations for breech-presenting babies is discussed by self-employed midwives Margaret Gardener and Jenny Crawshaw. Originally published in Birthspirit Midwifery Journal 2010; 5: 63-67. References updated March 2014.

The New Zealand Guidelines Group’s NZGG (2004) Care of women with breech presentation and previous caesarean section aims to provide accurate evidence-based information to health practitioners, pregnant women and their families about care with breech-presenting babies. The Guideline, containing summaries of the evidence that has been published on risks and benefits of either caesarean or vaginal breech birth in one document, can make it easier to weigh up risks and benefits and make decisions on the ‘mode of delivery’.

The New Zealand Guidelines Group’s NZGG (2004) Care of women with breech presentation and previous caesarean section aims to provide accurate evidence-based information to health practitioners, pregnant women and their families about care with breech-presenting babies. The Guideline, containing summaries of the evidence that has been published on risks and benefits of either caesarean or vaginal breech birth in one document, can make it easier to weigh up risks and benefits and make decisions on the ‘mode of delivery’.

The tertiary care unit in Otago, New Zealand, despite this Guideline, does not have any policies for offering and providing breech birth. Women are told that if they come into the birthing unit in labour, there will not necessarily be skilled clinicians on call at the time to provide care and, therefore, the safest option would be a caesarean section. Women planning a vaginal breech birth are also informed that the lack of experience or even exposure to breech birth amongst the clinicians at the hospital can be a significant factor in the standard of care they will receive there.

It is apparent that consultations that take place at the hospital ANC are not inclusive of the New Zealand Referral Guidelines Ministry of Health (2012) as breech presentation is not accepted as only an antenatal consultation. While it is not listed in Guidelines as requiring a labour and birth transfer of care, there is an obstetric assumption that breech presentation is an abnormal presentation and, as such, care is handed over. When the woman ‘fits’ within the criteria for a vaginal breech birth according to the algorithm, the NZGG recommends that an obstetrician be informed of the onset of labour and when active pushing commences but the woman’s LMC midwife continues with her care NZGG (2004, pp. 17-18). If labour progress slows or there is a concern regarding the mother or baby, a consultation is, of course, sought.

There is an emerging women-led trend that has been precipitated by the repercussions of the Term Breech Trial (TBT) Hannah et al (2000), that is, the dis-ease around vaginal breech birth. This article discusses the process started at Dunedin Hospital of trying to resolve women’s expressed feelings of being dissatisfied and feeling unsafe to birth their breech babies in hospital following ANC consultations, as Amy’s above story reflects, and to ease the tension felt by midwives who support women’s choices during breech birth.

What choices do women make?

Women will make a variety of choices when fully informed and cognisant of their options with their breech babies, even with the same information:

- Some are happy to accept the option of an elective caesarean section;

- Others comply to a caesarean, but feel they have been bullied or have no real choice;

- Some women wish to continue with a planned vaginal birth within the hospital setting;

- A subset of the women who wish to hospital birth feel they have no choice but to birth at home because of the conditions stipulated during a consultation in ANC (for example, compulsory epidural); and,

- A few women choose to birth their breech babies at home as a first choice.

It is the group of women who would ideally plan a hospital vaginal breech birth who are the most disadvantaged following the TBT trial. Most are highly motivated and well informed. The attitude they encounter is contrary to providing an atmosphere where they can birth physiologically in the hospital environment. If there is a perceived lack of compliance to a planned caesarean section, women are advised to return to ANC to try and procure the choice that is recommended to them.

Amy’s experience of the obstetric consultation process and the issues generated around the choices made available to her provided the challenge needed to look at what is actually going on for women birthing their breech babies. Amy was angry about her second antenatal consultation where she feels several sections of the Code of Rights Health and Disability Commissioner (1996) were breached.

When the Clinical Director was notified of this, she was concerned about the pathways that had led to Amy feeling that she was unable to safely birth at the hospital, stating “the hospital had failed this woman and [it] could do better for the woman choosing the path less travelled”. The Clinical Director went on to suggest a multidisciplinary meeting to discuss vaginal breech birth in the area.

The multi-disciplinary meeting

The multi-disciplinary meeting was well attended by obstetricians, registrars, and LMC and hospital midwives and went into extra time to accommodate the lively discussion. The meeting was skilfully mediated by the Clinical Director and all parties were given the opportunity to speak without being shouted down or demeaned.

The Clinical Director presented a summary of research that has dictated practice over the past 20 years. An LMC midwife presented an account of the journey a woman takes with her midwife when a breech presentation is confirmed, and the Code of Rights and the conflicting messages given to women. A hospital midwife presented her experience of breech births from early in her career where a breech presentation was viewed as a variation of normal to the present day where breech presentation is seen as an abnormal presentation. A speaker from the Ethics Department presented different ethical theories from the mother’s, baby’s and practitioner’s perspectives.

There was a wide range of experience from obstetricians in the room who had attended many breech births to practitioners who had never seen a vaginal breech birth. Few, either midwives or obstetricians, had attended a breech birth over the last year or two. The midwives who had attended breech births had done so in the community. It appeared that some of the more memorable births the experienced obstetricians had attended were breech births where the outcomes were poor.

A discussion ensued on safety and position for birth. All the obstetricians felt safer if a woman had an epidural and birthed in lithotomy. Most of the midwives felt safer with active birthing and birth in an upright position. One obstetrician did acknowledge that an epidural may mask some problems where a caesarean section was indicated. One midwife pointed out that the women who chose to birth vaginally in today’s environment were well informed and generally were choosing a physiological birth and the women who were prepared to have an epidural and lithotomy position, as a first option, would probably have chosen caesarean section.

The group was then asked to indicate if they were ‘comfortable’, ‘moderately comfortable’ or ‘very uncomfortable’ in ‘conducting’ a breech birth. The experienced obstetricians fell mainly into the comfortable category. Most of the other participants were either moderately comfortable, (but prefaced this with needing more experience), or they were very uncomfortable. Obstetricians who had recently qualified talked of very limited experience, and the accompanying limited confidence. Some of the more experienced obstetricians verbalised reluctance to the point of refusal to attend vaginal breech birth.

At the conclusion of the discussion there were divergent views from supporting woman to have a vaginal breech birth to only supporting an elective caesarean section. While caesarean section is now seen as a relatively safe operation, the midwives were concerned about the implications for future caesarean section. One talked about it as being seen as an “easy option” now but, for the woman with a subsequent pregnancy and requesting a vaginal birth after caesarean (VBAC), she is subjected to an often unpleasant consultation where she is informed of the increased risk of uterine rupture and strict criteria to “ensure the safety of mother and baby”. The language in these consultations varies but the words “dangerous” and “death of your baby” is used, and the ability to practice active birthing is reduced. A lot of the obstetricians present were surprised about this observation. The concerns around VBAC are already being discussed in another forum at the tertiary unit.